What is a medical doctor doing in a livestock research institute?

ILRI News

Posted on

Contributors

This is the question I posed to Abdoul Ilboudo, a medical doctor from Burkina Faso, when we met along the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) corridors in Nairobi. Ilboudo chuckled and offered a brief response peppered with words like 'Crimean-Congo virus', 'pandemic' and 'One Health'. Intrigued, I had a chat with him before his nine-hour flight back home. Here is what I discovered.

Background

Ilboudo hails from Burkina Faso, a French-speaking West African country. He knew early on that he wanted to help people, much like the doctors he had seen in his youth. Five years into his medical practice, however, a severe lack of medical supplies in the rural hospital where he had been posted frustrated him.

Then, at a conference, Ilboudo met a doctor in public health research who inspired him to pursue a master's in epidemiology and biostatistics. This move was to let him make a broader impact on his community's health, rather than treating patients as a general practitioner.

When COVID-19 hit Burkina Faso, as it had the rest of the world, the skills Ilboudo had gained while collecting throat and nose samples for his master's project came in handy. He had been studying what made acute respiratory infections like flu and respiratory syncytial virus become severe and fatal. This knowledge was invaluable when he was tasked to collect samples from the first COVID-19 patient in the country. He also played a key role in training and coordinating health workers through the Ministry of Health to collect and manage COVID-19 samples.

With his experience at his country’s Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé, Ilboudo embarked on a new mission. This time, it was to prevent a new virus from becoming the next pandemic – Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic fever (CCHF).

PhD research

Although lacking a background in livestock research, Ilboudo applied for a graduate PhD fellowship position at ILRI. His application was successful and he was awarded an in-country opportunity to study how people are exposed to CCHF in Burkina Faso.

‘Medical doctors work on humans; they rarely consider the spread of diseases from animals to humans,’ said the doctor-turned-scientist. 'I intended to bring my medical expertise into the field of One Health, which unites animal, human and environmental health.'

Like Ebola, CCHF causes fever and bleeding, and is thus referred to as a haemorrhagic fever. Apart from Asia, the Balkans and the Middle East, it is endemic in Africa, including Burkina Faso, and a CCHF outbreak has a fatality rate of 40 per cent.

Also like Ebola, CCHF can be transmitted from person to person. It can also be spread through tick bites, or close contact with infected blood or tissues. This shows the importance of animal-related research. Domestic animals such as sheep, goats and cattle can become infected by ticks carrying the CCHF virus, and complete the disease cycle by infecting more ticks.

Using a One Health approach, in addition to human, social and animal research components Ilboudo's research considers the environmental factors that contribute to the spread of CCHF. This includes the impact of climate change on tick populations and the emergence of new habitats suitable for ticks.

Mutual benefits with ILRI

At the time we met, Ilboudo was attending an advisory committee and graduate fellow meeting of the One Health Research, Education and Outreach Center in Africa (OHRECA) in Nairobi. During the meeting, he met One Health graduate fellows working in diverse research areas — antimicrobial resistance (AMR), zoonotic diseases such Rift Valley fever and rabies, and food safety.

'As a researcher based in west Africa, far from ILRI’s east African headquarters, participating in this workshop held at ILRI’s Nairobi campus allowed me to interact in person with my co-fellows, supervisors and stakeholders relevant to my study,’ the early-career scientist said.

Having achieved his dream of becoming a doctor, these days Ilboudo aspires to be a One Health expert, not only in his country but across Africa. He says the PhD fellowship is an invaluable opportunity to advance his career, citing a One-health Workshop in Burkina Faso in 2022 that drew experts from around the world, including the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) to whom he presented his project proposal ‘It enables me to meet and build a partnership with human and animal health authorities as well as researchers working in One Health.’

Ilboudo’s previous training and experience in observing and examining patients in rural West Africa brings a unique perspective to understanding how CCHF is transmitted. The results of this research will help create better prevention strategies and teach people how to protect themselves from CCHF. Perhaps this could even prevent another pandemic.

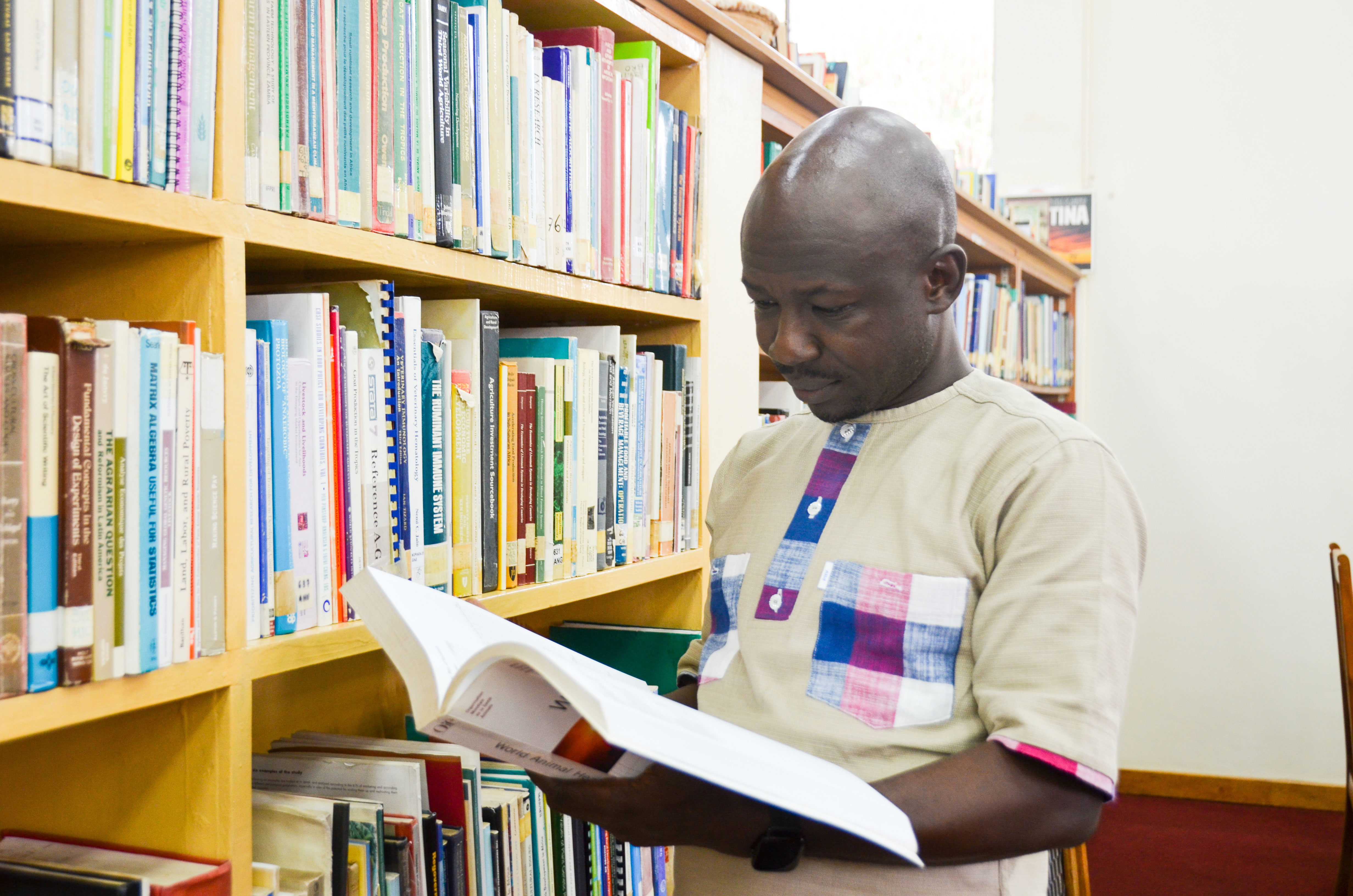

Abdoul Ilboudo along ILRI corridors. Photo by ILRI/Sarah Nyanchera Nyakeri

You may also like

ILRI News

Fostering collaboration between CGIAR and French institutions toward agriculture and health

ILRI News

Delia Grace Randolph appointed 'Honorary Doctor' by the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

ILRI News

Major ILRI-CGIAR-livestock contributions at the recent World One Health Congress in Cape Town

ILRI News

Building capacity for the next generation of One Health researchers: Insights from SEAOHUN fellows at ILRI

Related Publications

Integrated community-based reporting and field diagnostics for improved rabies surveillance in rural Laikipia, Kenya

- Odinga, Christian O.

- Thomas, Lian F.

- Wambugu, E.

- Ferguson, A.W.

- Fèvre, Eric M.

- Gibson, A.

- Hassell, James M.

- Muloi, Dishon M.

- Murray, S.

- Surmat, A.

- Mwai, P.M.

- Woodroffe, R.

- Ngatia, D.

- Gathura, P.M.

- Waitumbi, J.

- Worsley-Tonks, Katherine E.L.

Advocating for a participatory approach to One Health capacitation in Malawi

- Wood, C.

- Parker, L.

- Richards, Shauna

- Mutua, Florence K.

- Wawire, P.

- Munthali, B.

- Mtegha, C.

An operational framework for wildlife health in the One Health approach

- Goulet, C.

- Garine-Wichatitsky, M. de

- Chardonnet, P.

- Klerk, L.-M. de

- Kock, R.

- Muset, S.

- Suu-Ire, R.

- Caron, Alexandre