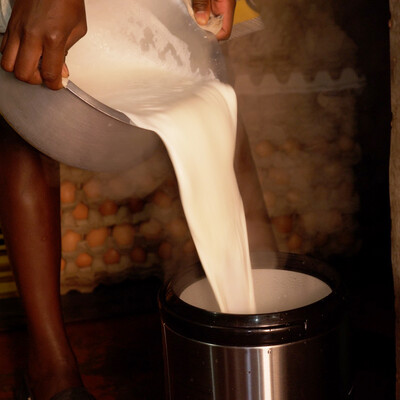

Milking it: boosting profit and professionalization in Kenya’s informal dairy sector

On the outskirts of Kenya’s Rift Valley town of Eldoret, many locals make money by selling fresh cow’s milk. Vendor Winnie Cherono (‘Mama Chumba’), who sells an assortment of staples from a small hole-in-the-wall kiosk, says her fresh milk is popular because it tastes better – and is healthier and cheaper – than the ultra-heat-treated (UHT) packaged alternative, which retails at around double the price.

More than 70 percent of Kenya’s milk is sold through outlets like this – kiosks and shops supplied directly by producers or through middlemen – in the informal market. But it’s not an easy enterprise. Most vendors don’t have fridges, so they need to sell all their stock on the day they receive it, and use careful hygiene and storage practices to slow down spoilage. Many also suspect that some of their suppliers also water their milk down or try to pass off older milk as fresh.

Government officials often push back on the unregulated informal sector with attempts to reduce, eliminate, or streamline it.

'The government has traditionally handled informal markets with a hard hand,' said Silvia Alonso, a principal scientist and epidemiologist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). 'They go around and inspect and if the vendors don't comply with requirements, they have to shut down.'

Whilst regulations are important to ensure the food sold in markets is safe for consumption, enforcing standards that are not aligned with current realities results in significant negative impacts on livelihoods – as well as on nutrition amongst poor households that can only afford milk from informal sources.

'A vast proportion of Kenyans depend on these markets, both as buyers and sellers, so it’s important to preserve them,' said Alonso.

That’s why Alonso’s team of ILRI scientists – in collaboration with the International Food Policy Research Institute, the International Institute for Environment and Development, and national partners – have been working with vendors in Kenya’s informal milk sector to help them up their game, through the More Milk project.

Pathways to professionalization

The team identified three key areas to improve the safety of any informal food sector: capacity building, incentives and an enabling environment. They designed a food safety intervention 'as a pathway to legitimize informal markets and informal actors while improving milk safety and hygiene practices – to find a way to bring them within the food systems rather than excluding them,' said Alonso.

The intervention aims to improve the safety of milk, increase milk consumption in children from low-income households, and enhance the vendors' revenues and professionalism.

The program has trained close to 200 participants in peri-urban Eldoret. They learned to evaluate freshly delivered milk in their shops using simple tests – organoleptically (that is, using the senses to assess flavour, odour, appearance, and texture) and by boiling it to assess its freshness, purity, and safety. They also received training on milk handling (such as ensuring containers are uncontaminated), business skills, ‘soft skills’ like negotiation with suppliers and customers, and product promotion – including implementing a marketing campaign to promote the importance of milk for children and build better connections between vendors and consumers.

Value-addition sessions shared methods for making buttermilk (maziwa lala in Kiswahili) and yoghurt – both of which present great options for using up unsold stock before it spoils. The trainers also visited each vendor regularly to test their milk and provide feedback and coaching.

What they learned so far

The intervention’s success is being evaluated through a field experiment that’s tracking improvements in food safety amongst vendors who participated in the project (by testing samples of the milk being sold), and milk consumption among children in the surrounding households, in comparison to their counterparts in a group who didn’t receive any training. Emerging findings suggest positive impacts.

'We can tell that the intervention has had a lot of impact for the vendors we've been working with, especially in terms of milk hygiene practices,' said Emily Kilonzi, a research associate in ILRI’s MoreMilk project. 'They have learned things that they might have heard about before the project but had not been doing, and other things that were completely new to them – particularly about how they should handle milk in their premises and communicate to their customers.'

Customers are reporting increased confidence in vendors, whom they see as more competent and knowledgeable about supplying safe, high-quality milk. 'Some of the vendors are saying that they're selling more, have better customers and are able to get better milk from the suppliers,' said Alonso.

Opportunities for women

Meet Loice Jemutai – a 26-year-old vendor and mother-of-two who sells fresh milk in her shop in Kapsaret Region. Jemutai has been running her business since 2017, and was motivated to participate in the training because the milk from her suppliers was going bad quickly – and her customers were complaining.

After learning how to test the quality of the milk, Jemutai realised she was often receiving old and watered-down milk. She switched suppliers and now gets milk directly from a farm, where she carries out inspections and instructs the farmer on hygiene practices. She also educates her customers on food safety, advising them to bring clean containers to carry their milk home, and shares her knowledge with other vendors in the area.

Jemutai says that selling milk is rewarding, though it requires “total commitment”, creativity, and careful planning – particularly for women who tend to have many family responsibilities to fulfill.

'I must plan my day well, so the milk does not go bad,' she said. 'I take the children to school early in the morning and come back to open the shop so the suppliers can find me open.'

Kenya’s women are disproportionately affected by poverty, and the sector offers a unique business opportunity for those with limited resources because of the minimal financial input required. Done well, interventions like MoreMilk can help to empower vulnerable women through better livelihoods, the increased confidence associated with professionalization, and improved nutrition for their families – a vast contrast from the impacts of a repressive approach to informal markets, which is more frequently used by governments in low- and middle-income countries.

'When you adopt a process of coaching and supporting people to help them transform, there are a lot of benefits,' said Alonso. 'This suggests that governments should rethink their approach to engaging with informal markets, because we’re showing that with the right support, hygiene practices can change and vendors can begin on a path to formalization.'

Learn more

- Paper: Milk purchase and consumption patterns in peri-urban low-income households in Kenya(February 2023)

- Paper: Gendered barriers and opportunities in Kenya's informal dairy sector: enhancing gender-equity in urban markets(June 2022)

For information contact s.alonso[at]cgiar.org.

All photos by ILRI/Kabir Dhanji taken in Kenya's highland region of Eldoret. Banner photo: Winnie Cherono, fondly called 'Mama Chumba', prepping milk in her shop to test it for freshness and fat content.