Can Kenya meet dairy production and greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets by 2030?

Kenya, like many African nations, faces the challenge of increasing dairy production to meet future demand while also reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, as population growth and dietary preferences shift towards greater consumption of animal products.

While livestock production is a significant source of GHG emissions, it is also fundamental to achieving several other Sustainable Development Goals, including ending poverty, combating hunger and ensuring food security, promoting good health and well-being, and supporting decent work and economic growth.

Efficient livestock production systems need to be identified to meet this challenge. However, there is a lack of local data on livestock productivity and GHG emissions, as well as knowledge on the effect of locally appropriate interventions on livestock productivity and GHG emissions.

To help fill this gap, researchers at the International Livestock Research Institute's Mazingira Centre, in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) conducted a study of smallholder dairy systems in Kenya's Rift Valley region.

They sought data for the following questions:

What are the current and potential milk yields in Kenya’s Rift Valley region?

The researchers collected data about current milk yields from 176 adult female cows across the four dominant agro-ecological zones in Kenya’s Rift Valley region. They calculated the yield gap by comparing the yield of the top 10% most productive cows in each agro-ecological zone, to the average yield of all of the cows in that zone.

The findings showed that substantial yield gaps exist in Kenyan dairy systems, estimated at 39 to 49% of attainable yields, depending on the agro-ecological zone.

Can milk yield gaps be closed with locally appropriate, evidence-based interventions?

The researchers tested five interventions aimed at increasing productivity and reducing GHG emissions. These interventions were chosen as there was existing local data showing their capacity to reduce emissions while increasing productivity in Kenya:

- Decreasing the age at first calving

- Increasing fertility rates

- Supplementing with sweet potato vine silage

- Supplementing with dairy concentrate

- Increasing overall feeding levels

These interventions were also combined into four packages that tested the effect of implementing multiple interventions at once to maximize productivity and GHG mitigation.

The researchers found that from individual interventions, increasing fertility rates had the most significant effect, closing the milk yield gap (22-32.6%), followed by supplementing with sweet potato vine silage (20.2-29.9%) and increasing feeding levels (17.9-26.4%).

Decreasing the age at first calving had the lowest impact (0.7-26.4%). Combining interventions yielded the best results, with most packages exceeding 100% of attainable yields across all agro-ecological zones.

Can these interventions help the country meet its national targets for 2030?

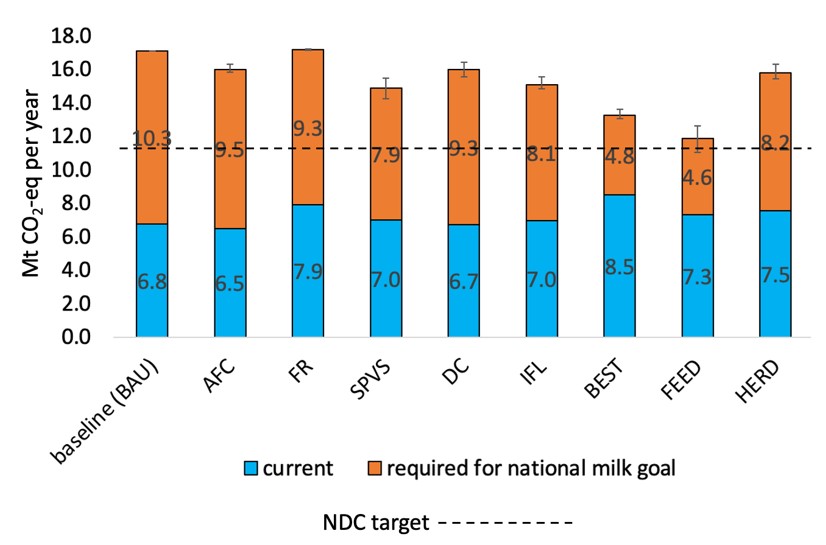

The researchers could assess the effect of interventions on absolute emissions and emissions intensity at the national level by scaling up the individual agro-ecological zones in the Rift Valley. The zones are representative of major dairy production regions of Kenya, so scaling up was done by including all cows found in similar zones throughout the country. To calculate absolute emissions and emission intensities, the FAO’s Global Livestock Environmental Assessment Model – interactive tool (GLEAM-i) was used. GLEAM-i is an online tool that allows for assessments of GHG emissions throughout the livestock supply chain.

Results using GLEAM-i showed that absolute emissions increased in most scenarios, except when applying the reduced age at first calving and supplementation with dairy concentrate intervention, which reduced absolute emissions slightly.

All interventions resulted in a reduction in emission intensity—the amount of GHG produced per unit of product, in this case milk.

The individual interventions producing the largest reduction were supplementation with sweet potato vine silage (reduction of 11.3%), followed by increased feeding level, where emissions intensity (reduction of 10.3%).

But combined packages were the most effective at reducing emission intensities, with the ‘best bet’ (increased fertility rate + sweet potato vine silage + increased feeding level), ‘herd management’ (age at first calving + increased fertility rate) and ‘feed management’ (sweet potato vine silage + dairy concentrate supplementation + increased feeding level) packages reducing emission intensities by 26.6%, 13.0%, and 27.4%, respectively.

All interventions reduced milk yield gaps. Decreased age at first calving and increased fertility rates meant shorter time periods when cows would not be producing milk. Feeding interventions generally increased feed quality and so subsequent milk yield.

Overall, these intervention scenarios show that it may be possible to meet Kenyan national milk production and GHG emission goals by 2030.

What next?

To meet national production targets, Kenya must increase milk production by 150% by 2030. Without increasing productivity per cow this target can only be reached by increasing cattle numbers from 2.7 million in 2010 to 7.1 million by 2030. But they may not need to increase numbers as much if productivity can be improved.

In addition, the Kenyan government also has the GHG emission reduction target of 32%.

The study found that if farmers adopted the packages with multiple interventions, production and mitigation targets could be reached. Further research is needed to gauge farmer’s interest in these interventions and the accessibility of such options.

The study was funded through the CGIAR Initiatives on Livestock and Climate and Low Emissions Food Systems” We thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund. Furthermore, the study builds on data generated during the GIZ-funded Program for Climate-Smart Livestock (PCSL, Program No. 2017.0119.2) and the IFAD-funded project Greening livestock: Incentive-based interventions for reducing the climate impact of livestock in East Africa (Grant No. 2000000994).

You may also like

Opinion and analysis

Sustainable manure management in Uganda requires an enabling policy and legal framework: a call to action!

ILRI News

ILRI introduces the Livestock and Climate Solutions Hub at SAADC 2025 to address climate challenges in livestock systems

ILRI News

When policy meets pasture: Farmers and scientists joining forces to shape a fair climate future

Related Publications

Systematic review on the impacts of community-based sheep breeding programs on animal productivity, food security, women’s empowerment, and identification of interventions for climate-smart systems under the extensive production system in Ethiopia

- Tesfa, Assemu

- Taye, Mengistie

- Haile, Aynalem

- Nigussie, Zerihun

- Najjar, Dina

- Mekuriaw, Shigdaf

- Dijk, Suzanne V

- Wassie, Shimels E

- Wilkes, Andreas

- Solomon, Dawit

Genetic relationships among resilience, fertility and milk production traits in crossbred dairy cows performing in sub-Saharan Africa

- Oloo, Richard Dooso

- Mrode, Raphael A.

- Ekine-Dzivenu, Chinyere C.

- Ojango, Julie M.K.

- Bennewitz, J.

- Gebreyohanes, Gebregziabher

- Okeyo Mwai, Ally

- Chagunda, M.G.G.

The impact of heat stress on growth and resilience phenotypes of sheep raised in a semi-arid environment of sub-Saharan Africa

- Oyieng, Edwin P.

- Ojango, Julie M.K.

- Gauly, M.

- Ekine-Dzivenu, Chinyere C.

- Mrode, Raphael A.

- Clark, E.L.

- Dooso, Richard

- König, S.

Ambient environmental conditions and active outdoor play in the context of climate change: A systematic review and meta-synthesis

- Lee, E.-Y.

- Park, S.

- Kim, Y.-B.

- Liu, H.

- Mistry, P.

- Nguyen, K.

- Oh, Y.

- James, M.E.

- Lam, Steven

- Lannoy, L. de

- Larouche, R.

- Manyanga, T.

- Morrison, S.A.

- Prince, S.A.

- Ross-White, A.

- Vanderloo, L.M.

- Wachira, L.-J.

- Tremblay, M.S.