Using ethnography to understand gender dynamics in poultry farming

Melanie Ramasawmy is a researcher at the University of Roehampton, London. She is working on the Going Places Project, which is looking at women and chicken husbandry in Ethiopia. The project builds on her PhD research on ‘Do chickens dream only of grain?’, which looked at the role of chickens in the household and their relationship with gender, status and the domestic economy. Ramasawmy holds a BA in archaeology and anthropology (University of Cambridge) and MSc in anthropology and ecology of Development (University College London). The following is a summary of an interview she gave about her work in the project.

What are you currently working on in the Going Places Project?

The Going Places Project is looking at ways of empowering Ethiopia women poultry farmers. To achieve this goal, we need to understand their experiences and challenges in poultry farming; especially when doing it as a business. As part of this goal, I am conducting an ethnographic study and have been doing separate group interviews with male and female farmers. I have also been conducting in-depth individual interviews with women. We are looking at various aspects of poultry keeping and care such as decision-making roles, division of labour, consumption patterns and preferences. We also want to know the sources of information people turn to, what kind of information they would like to receive in the future and the type of interventions they feel would be more beneficial. The final aspect of the study looks at the role of chickens in local cultures through the analysis of local idioms.

Where are you conducting these interviews?

The initial plan was to do interviews both in Addis Ababa and Tigray regions. But since the field visits were relatively short, it made more sense to make four field visits in the Addis Ababa area. Therefore, we have selected and conducted the interviews in four peri-urban Addis Ababa locations.

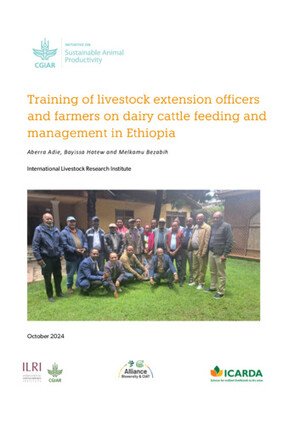

Melanie Ramasawmy conducts group interview with women poultry farmers in peri-urban Addis Ababa (photo credit: ILRI/Michael Tsegaye).

It is a pilot project and we have designed it with the view that it is worthwhile to do something in-depth in one region rather than visit four villages in four different regions, which would not be representative.

How reflective of the other regions do you think the selected sites are?

Obviously things will differ from region to region and I would not say you can directly apply the finding of this research to all other regions. But I think there are always cultural similarities between regions in issues like consumption and so on. There also might be similarities between women’s role in households, the attitude related to keeping a few number of chickens in the house and how it might change when the flock grows and is considered a business.

You said you are researching idioms and sayings, how does it help you in your objective of empowering women?

I think idioms can provide useful insight to attitudes. They can be indicative of cultural thinking and practices towards women and cultural attitudes towards animals. There are also a few sayings and phrases which directly compare women to chickens and that is an interesting thing to understand. Also, when you are writing to audiences outside Ethiopia, these saying can be a useful tool for communicating these relationships.

What has been surprising to you so far?

I have been surprised by the degree to which women who see themselves as relatively urban feel these strong relationships with chickens. They often declare that they see and love individual chickens like their own children. I was not expecting this kind of sentiment because most of these households have received 25 exotic birds as part of the African Chicken Genetic Gains project, which in my previous field experience, were often described as not exactly being chickens. Even though these are different types of chickens than what they are used to, they are still attached to them.

What have you noticed about the relationship men have with poultry production?

In other economies, as poultry production becomes more beneficial, men have started to be more involved and eventually take the benefits away from women. This especially happens in peri-urban settings where people cannot keep larger livestock and in countries where there is a strong gender preference to what livestock to own; chickens and small ruminants for women and cattle for men.

Programs that have started using chickens as a means of empowering women have inadvertently ended up benefiting the men more than the women. So, part of the rationale of our study is to understand the situation in Ethiopia better so we can enable women to keep control of chicken production. This is part of the reason why we were also interviewing men. We wanted to understand if they believe that there are local reasons for why men end up owning the larger chicken businesses. I have seen this happen in my previous research. To some extent, you can see the same thing happening but there are a few women who are really interested in developing a poultry business. Hopefully, one of the outcomes of this research will be recommendations on how to help women overcome the barriers and become the beneficiaries of poultry businesses.

What was surprising for you about the men in poultry production?

No surprises. The men usually have similar views. Men do not vocalize the barriers women face as cultural and will see them as practical; when in fact they are mostly cultural. We have been asking the women to tell us how involved their husbands have been in poultry keeping, and while there are households where the men do not get involved unless absolutely necessary, many have said that there are points where the husbands will assist, like when the wives are pregnant, taking care of babies or when they are sick. A few women have said their husbands willingly assist and love the chickens as much as they do.

What are the expected outcomes of this study?

We expect a few outputs from this research.

The first output will be the production of a couple of short videos we hope to finish by June 2017. The videos will be about women’s experiences and relationships with chicken. They will showcase the women farmers talking about their challenges, opportunities and also their individual relationships with the birds.

As a second output, depending on availability of funding, we are thinking of publishing a book that will include the portraits of the women and some excerpts of the interviews. The book would be an ethnographic output.

We are also working with Alessandra Galie, a social scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), to write up a report for ACGG. The report will cover outcomes of the study and will forward recommendations to the larger ACGG project.

The fourth and last planned output is educational materials that will share information the respondents of the study told us they need.

We have also planned a ‘family day’ in June 2017 and we will have all four outputs by then.

What are you planning to achieve during the family day?

The family day approach is something we have done in the UK as part of the larger Cultural and Scientific Perceptions of Human-Chicken Interactions Project. The idea is that a family day held at ILRI could be the main engagement output; this might combine a number of different activities, depending on cost and space available. It will use a mixture of activities to get engage children with some of the science in a fun way. It will also give us a chance to showcase the materials we will have. Moreover, we will be working with the National Museum educators to train them on how to run similar family days. All in all, we will be using it to bring together all stakeholders of the project, including the farmers we work with.