Pandemic preparedness: The lessons of One Health

One Health is not an approach which is limited to zoonotic disease outbreaks, said Kristina Roesel, scientist in the Animal and Human Health program at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), as she delivered a keynote talk at the ‘Workshop on One Health with a focus on prevention of pandemics’. The event was organized by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) on 12 May 2020.

Instead, One Health is a day-to-day and very practical concept. It is already well understood by the 200 million pastoralists worldwide, who must rely on the health of their livestock and the environment to support the health of their family, she said.

Measures to contain the pandemic have put additional strain on people in low-income countries who work in jobs without social security or health insurance. This means that like the One Health approach, a balance needs to be found between measures to contain the pandemic, and measures intended to avoid even more harmful consequences, such as hunger or riots.

So to prepare for pandemics in low income countries, we need to consider other chronic problems that make people vulnerable, said Roesel.

She suggested an early warning system of disease surveillance, by capturing clinical symptoms in humans and animals throughout communities. If the frequency of certain symptoms increased, then an in-depth investigation would be carried out. So, although the poorly developed veterinary sector is currently part of the problem, it is also a potential solution. Surveillance could be carried out at the level of livestock production, as well as slaughter and should be linked to syndromic surveillance in people.

But this is easier said than done, admitted Roesel. In Germany, there is a veterinarian to livestock ratio of 1:2000. Yet in Kenya alone the ratio is 1:16000, and distances between smallholder farms are vast. NGOs like Vétérinaires sans frontières are indispensable in maintaining veterinary coverage, but timely diagnosis and prevention are limited by a lack of quick tests and thermostable vaccines to dispense.

Roesel also described how vets who travel to farms can end up dispensing health resources to humans. This suggests that resources in the health sector could be shared and combined.

There are numerous health issues largely limited to poor countries of the tropics and subtropics, which can increase susceptibility to infectious diseases. Soil-transmitted worms infect about one quarter of the world population, and kill 150,000 people each year, especially children. According to the WHO foodborne illnesses reach the same amount of people as malaria, and TB and HIV reach the same order of magnitude.

With at least 80 per cent of food in low-income countries bought and sold in informal markets, this poses challenges for abattoir surveillance and food inspection. Roesel said this informality also characterizes the pharmaceutical sector, with many drugs available without prescription and dispensed by unlicensed personnel.

One Health also includes the environment, the health of ecosystems. Exploitation of natural landscapes and land use change increases possibilities of transmission of diseases from wildlife to livestock and humans. Similarly, climate change can exacerbate animal health problems by creating conditions that spread parasites and pathogens, or lower water availability and raise heat stress. Improving animal health enhances productivity and reduces animals lost to disease, both of which mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

Incentives could be a solution, suggested Roesel. She gave the example of African swine fever. Currently farmers receive no governmental compensation for losses, and therefore have little motivation to report an outbreak. Instead, upon hearing rumors of a nearby outbreak, farmers will sell their animals immediately and inadvertently contribute to faster spread of the disease. This problem could be met with mobile laboratories, on-site quick tests, and compensation incentives. Regarding existing zoonotic diseases like Rift Valley Fever, she also noted that high-income countries should take the opportunity now to prepare for potential pandemics that will have their origins in low-income countries.

One Health must be clearly defined so that stakeholders have equal understanding and can see its advantages, Roesel recommended. Human health is not the only goal of the work, and animals and the environment should not be investigated only as part of the problem. One Health covers animal welfare and health, ecosystem health, interconnectedness with climate change, and political, economic and societal health. It recognizes these elements as equal.

The majority of emerging infectious diseases originates in southeast Asia, caused by the density of wet markets, livestock and humans. But this trend can also be observed in Africa where the human population is estimated to double by 2050. Consequently, One Health has been well established in some countries of Southeast Asia, including Vietnam and Thailand, and partly supported by the BMZ.

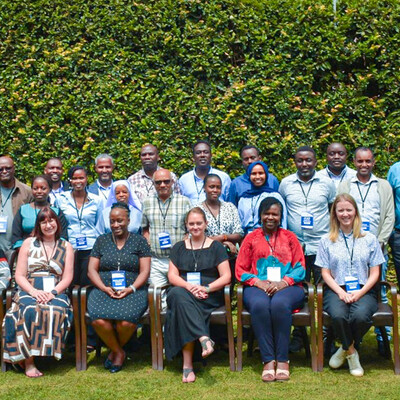

Roesel closed by saying that the BMZ has long supported ILRI’s mission of ‘research for development’, of which One Health has been an integral part for over 15 years. With the building of the new ILRI/BMZ One Health Centre for Africa in Nairobi, she hoped that this work would be taken to larger scales.

Kristina Roesel’s keynote speech was developed with input from colleagues Sonja Leitner, Lutz Merbold, Dieter Schillinger, Fred Unger, and Barbara Wieland.