New study identifies equity gaps in informal milk sector and highlights the need for gender-transformative approaches in development interventions

On 27 June 2022, a paper titled ‘Gendered barriers and opportunities in Kenya’s informal dairy sector: enhancing gender-equity in urban markets’ was published in Gender, Technology and Development. The study, led by International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) Gender Scientist Alessandra Galiè, aimed to understand the gendered constraints and opportunities in Kenya's informal dairy sector. It identified some key challenges that result in a more profitable experience for older males than their female counterparts and young men. The findings also raise important questions about the sustainability and viability of development interventions aiming to enhance equity within the dairy sector.

For many women in LMICs, informal markets are where they can participate in business enterprises. Because of the low input costs required in the informal milk sector, the industry poses a unique opportunity for women (and men) to generate income. The study, consisting of approximately one-hundred interviews with men and women across the milk value chain, found that gender dynamics and norms, age, marital and economic status limited women's ability to stay in business, despite the numerous opportunities and overall [lack of?] satisfaction.

Some key factors affecting the lucrativeness of the milk industry for traders are low purchase prices, the ability to sell milk in larger quantities, and safe milk—all of which are increased if traders can source directly from producers. However, the challenge for women, who are also customarily responsible for domestic work, is just that. For instance, to source milk from producers, women must travel in the early morning hours, when married women typically prepare breakfast and prepare their children for school. Women are also usually discouraged from travelling and cannot reach rural areas where most producers are located. Women are also often unable to carry the heavy metal containers required to transport milk long distances, limiting the amount of milk they can transport at a time. And because of these constraints—of which there are more—women cannot fully participate across the different nodes of the value chain, so they become retailers who get milk delivered from middlemen. But this also poses a challenge. By the time milk is delivered to their shops, it has travelled through various intermediaries, increasing the odds of spoilage and resulting in milk losses, or more importantly, income. Young men face similar issues but can overcome them as they grow older.

The findings raise important questions about the design and implementation of development interventions like the ‘MoreMilk: Making the most of milk' project led by ILRI, which provided technical support to retailers for enhancing milk safety. Some of the feedback from women during the project, which this study aims to support, revealed feelings of being disadvantaged in the industry by their negotiation power and lack of access to credit. Ideally, these challenges can be addressed by incorporating elements like gender-responsive training to address those business constraints. But while this may improve their business opportunities, the real question is about whether these interventions are a sustainable solution if the 'root causes' of inequity aren't addressed. For example, should interventions accept and accommodate social norms, or should they engage in ‘gender transformative approaches’ (GTAs), or in other words, deal with these norms? Should a project support milk delivery to women because of gender-based restrictions on mobility or, rather, should it work with the community to challenge the value of such restrictions?

‘We do not have a blueprint approach to gender interventions. We engage the communities—their women, men, girls and boys—to discuss their views, challenges, and aspirations for their livestock-based livelihoods. We then discuss how to best address challenges and leverage opportunities. Approaches may be accommodative, transformative, or a combination of both. Our approaches may also change during the life of a project as we try an intervention and realize how to best adjust it,’ said Galie.

For researchers, engaging in GTAs is more so a challenge of priorities and budgets. According to Galiè, projects interested in integrating gender issues may not necessarily dedicate a budget to a gender scientist, gender analysis, or gender-focused activities—which limits the scope of the gender work they can do.

On the other hand, there is also the issue of persuading experts that gender issues, frequently dropped from the final prioritization of challenges to address during an intervention, should remain a priority. And finally, in cases where gender issues are identified and prioritized for intervention, the project may be of a 'technical nature' – e.g. focused on genetics or health – and may not fund an intervention with a strong gender focus by considering it beyond its main scope. Yet, a project that disadvantages its women stakeholders will never completely serve all of its beneficiaries.

This study, which will help participating scientists develop a framework that informs the MoreMilk project (and highlights the gender constraints faced by women in the informal milk sector), underscores the importance of gender-transformative approaches in development interventions. 'Any development intervention transforms communities and culture: introducing new machinery, forage varieties, and markets all affect how things are done in the household and community and by whom. They all affect women, men, girls and boys differently.' said Galiè.

'Gender transformative approaches ensure that no one is affected negatively by the intervention and that all benefit as much as possible. It does so by engaging the community in discussing how they see change, tradition and local culture and envision their future. Gender transformative approaches have the ethics of equity and sustainability at their core.’

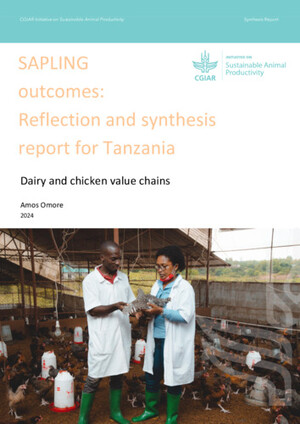

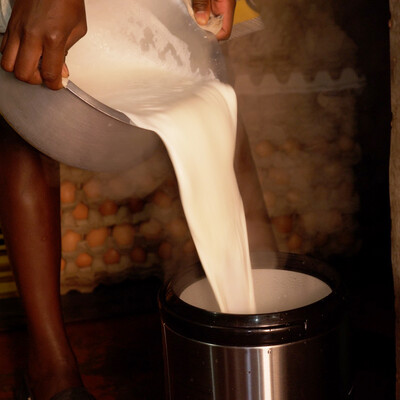

Lilian Satia, a young dairy entrepreneur in Nakuru, Kenya has started a milk bar with other youth. (photo credit: ILRI/Georgina Smith)