Farmer finds a sweet spot producing orange-fleshed sweet potato vines and roots during the dry season in Zambia

Down in the valley in the village of Kasuza in the Eastern Province of Zambia, along the border with Mozambique, Aaron and Mervis Mumba are legends. The couple, who have two children, are literally turning on its head the negative connotation associated with the phrase ‘reaping where you did not sow’.

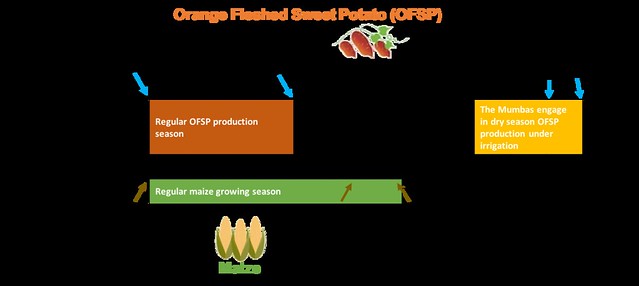

Through meticulous analysis of the farming season, a careful comparison of the costs of production for maize and orange-fleshed sweet potato (OFSP), certified understanding of the demand and supply market forces at play in their village, and a reliable barter trade system amongst farmers in their village, this family has hit the jackpot because of shifting to dry-season OFSP farming.

Aaron and Mavis Mumba with their two children in front of the house. Photo credit: Simon Mudenda/CIP.

Revelation at first attempt

A government extension agent holds up big OFSP roots harvested from the Mumbas’ farm during a field visit organized by the Africa RISING project team. Photo credit: Simon Mudenda/CIP.

The Mumbas had always been subsistence farmers, growing various crops such as maize, soybean, cassava, and sweet potato (non-OFSP). Things changed in September 2014 after Aaron joined several other farmers in partners’ meeting organized by the International Potato Center (CIP) and the Zambian Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI). This would mark a shift in his practice of farming—from subsistence to a commercial venture. At the meeting, CIP was recruiting OFSP vine multipliers and Aaron volunteered. The rest, as they say, is history and Aaron and Mervis have never looked back. They still grow other crops for subsistence needs but OFSP production (for roots and vines) is now their mainstay commercial agricultural venture, thanks to the demand occasioned by the community’s appreciation of the great taste and nutritional value of OFSP.

From the family’s 1.5 ha piece of land, they grow OFSP variety Olympia on only 0.25 ha but it is this small area under OFSP that offers the most returns! It was a case of revelation at first attempt when, at the end of the 2014/2015 season, the Mumbas bartered 200 bags of OFSP vines and roots for 10,000 kg of maize. The prevailing barter exchange terms in that season were as follows: a bag of OFSP vines or roots for a 50-kg bag of maize.

‘That 2014/2015 season was a revelation to us,’ Aaron says. ‘We couldn’t have grown and harvested nearly as much maize as I gained from this barter exchange with different farmers in my village. Because the vines and roots were in demand and I was the only supplier, we got very good returns!’

Learning fast, making smart moves

Learning very fast and benefiting from advice offered by CIP and other partners working under the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded Africa RISING going to scale in the Eastern Province of Zambia Project, Aaron and Mervis had an idea. If they could harness the underground water that was easily accessible at their farm, thanks to a high-water table, they could start dry-season vine production. This move, they expected, would ensure that they would have vines (in high demand) ready to be bartered to fellow farmers at the onset of the rainy season when a majority of them would again be looking for OFSP vines to plant. At a cost of 400 bundles of OFSP vines, Aaron purchased a treadle pump from the project team and began vine and root production of OFSP under residual moisture and irrigation.

When the 2015/2016 rainy season came, the Mumbas were ready with their full grown vines to barter trade with their fellow farmers. However, this time it was not a direct exchange of goods because the planting season was just commencing and no farmer had maize to offer in immediate exchange. After agreeing on the terms of the barter trade with every interested farmer in the village, Aaron and Mervis supplied the vines ready for planting. During the 2015/2016 harvest season, each farmer came back and settled accounts with them.

Better returns per hectare of OFSP

They have realized that they are better off growing a small portion of OFSP (0.25 ha) which earns them as much as 10,000kg of maize when bartered (as happened in the 2015/2016 season). According to the Zambian Food Reserve Agency, in that same season (2015/2016) prices ranged between ZMW 85 and ZMW 100 (USD 0.3) / 50 kg bag of maize.

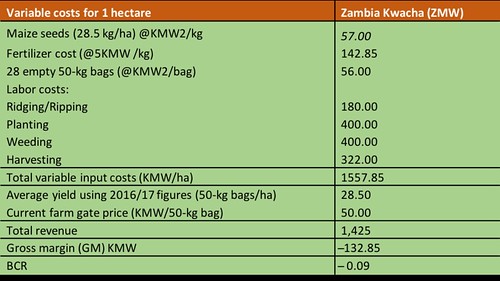

Table 1. Profitability analysis for maize production by the Mumbas

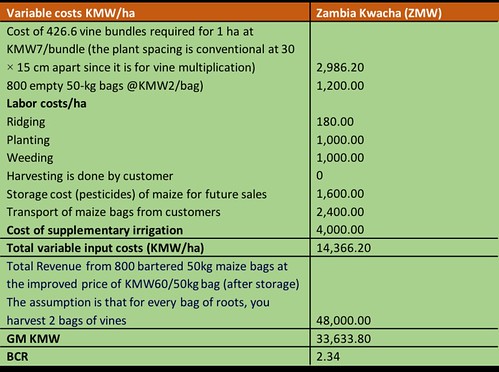

Table 2. Profitability analysis for sweet potato production by the Mumbas

Comparing the maize and OFSP enterprises, a profitability analysis revealed a higher gross margin for sweet potato (ZMW 33,633.80) than for maize (ZMW ̶132.85) on a per ha basis. This indicates a BCR (Benefits Cost Ratio) of 2.34 for OFSP and ̶0.09 for maize. Therefore, for every ZMW 1 the Mumbas spend on growing OFSP they gain a benefit of ZMW 2.34 more, unlike their comparative loss of ZMW ̶0.09 realized from growing maize.

Future outlook in the face of changing weather patterns

The effects of changing weather patterns have, however, not spared the Mumbas. Poor rainfall in the 2015/2016 seasons negatively affected their dry-season production of roots and vines as their shallow wells dried up. Because of low productivity, they earned ZMW 2,550 from bartering only thirty 50 kg bags in 2016 from the dry-season production of the previous season. Still this income was good enough for the family to be able to buy other food stuff that they did not grow that year. For 2017, from OFSP vines produced in the 2016 dry season, they bartered 130 50kg bags of maize.

‘I am thankful that we got into this OFSP vine and root production venture,’ Mervis says. ‘It is changing our lives for the better. We have been able to build a house and are now planning to save up and buy a car that will enable us to expand our vine supply even to neighbouring villages. We are still learning new things as we go along.’

The Mumbas’ success story highlights how improved agricultural technologies placed in the hands of innovative ‘lead’ farmers can lead to significant improvement in livelihoods, ensure widespread scaling of improved agricultural technologies, and ensure farmer-friendly value chains that respond to localized community needs’ development.

The Africa RISING going to scale in Eastern Province of Zambia project is working to spread the OFSP and other improved agricultural technologies through various approaches and channels. In the OFSP scaling strategy, lead farmers such as Mervis and Aaron are known as decentralized vine multipliers (DVMs) who supply OFSP vine to their ‘local’ communities. Currently the project is working with 214 DVMs through an intricate and strategic network that ensures sweet potato planting material moves from the research stations to the farmers.

Writers and contributors: Jonathan Odhong’, Felistus Chipungu and Simon Mudenda