DNA sequencing of indigenous African cattle reveals vital clues to increasing productivity

Since their introduction to Africa thousands of years ago from the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent, cattle breeds have gradually adapted to cope with hugely varying environments, from the Sahelian desert to the subhumid tropical forests. These cattle are important sources of meat, milk, traction and manure across the continent. With rapid population growth and a rising urban middle class, they will become even more significant as demand for meat and milk is expected to more than double in sub-Saharan Africa from 2000 to 2030.

Since their introduction to Africa thousands of years ago from the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent, cattle breeds have gradually adapted to cope with hugely varying environments, from the Sahelian desert to the subhumid tropical forests. These cattle are important sources of meat, milk, traction and manure across the continent. With rapid population growth and a rising urban middle class, they will become even more significant as demand for meat and milk is expected to more than double in sub-Saharan Africa from 2000 to 2030.

Identifying the genetic basis underlying heat tolerance and resistance to killer diseases—major production constraints—offers huge opportunities to increase meat and milk productivity to meet rising demand. It opens the way to the scaling up of breeding programs for these specific key traits, potentially enhancing the incomes of hundreds of millions of smallholders worldwide.

Conserving the genetic diversity of farm animals and promoting access to, and fair and equitable sharing of, benefits arising from such resources(Photo credit: ILRI/Bethlehem Alemu and Apollo Habtamu)

The greatest challenges facing researchers are cost and time. Though the cost has dropped in recent years, the opportunity to explore this treasure trove may be short lived, as the nature of cattle breeding on the continent today is contributing to a significant loss of diversity. Africa is witnessing major transformations of its agricultural systems and rapid loss of indigenous livestock, representing an irreversible loss of unique traits that may serve as vital insurance against future challenges, such as increasing drought or emerging pests.

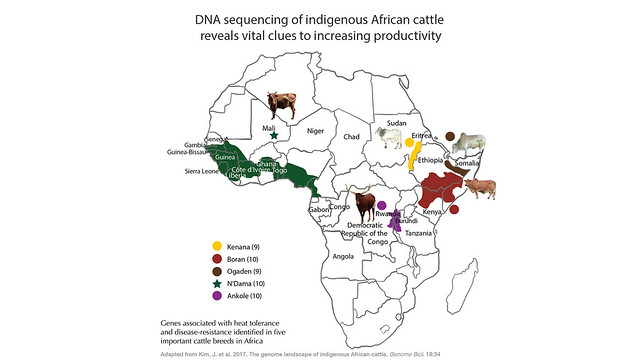

Conscious of these challenges, scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and partners selected five of the 150 breeds of cattle in Africa—analysing DNA samples of 48 animals—based on their economic importance to smallholders, representativeness of the sample to each breed and geographical spread throughout the continent. They analysed the genome of each animal and looked for characteristics particular to the breed. And their ground-breaking findings identifying useful genetic adaptations have justified the decision to proceed with a relatively small number of breeds.

Scientists pinpointed the specific genes involved in helping African cattle cope with rising temperatures and disease, such as the tsetse-fly-transmitted trypanosomiasis which in Africa has been estimated to cause up to USD4.5 billion in annual losses due to illness and death. They then generated a catalogue of genetic variants in the breeds and identified the unique DNA of each breed that gives them an advantage.

Genes were identified associated with feeding capacity under tropical climatic conditions in the West African taurine N’Dama, horn development and coat colour in the Central African Ankole, and heat tolerance in the three zebu breeds (Boran, Ogaden and Kenana) from East Africa. Genes associated with tick resistance were also identified in all five breeds. The findings will better inform breeding and crossbreeding programs designed to improve cattle productivity and resilience in sub-Saharan Africa, while preserving the unique genes in these indigenous cattle species.

These findings have helped scientists secure funding to undertake the DNA sequencing of a further 50 cattle, chicken and sheep breeds. In line with the Nagoya protocol to the Convention on Biological Diversity on fair access to and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources, ILRI’s broader aim is to catalogue the genetic information on all 10,000 breeds of domestic livestock in the world before that diversity disappears. The good news is that the exciting new science of genomics enables geneticists to unravel the genetic make-up of cattle breeds and to identify, and breed for, those traits best suited to the world’s diverse environments, while helping government institutions conserve this precious diversity. This work would cost approximately USD70 million, a small investment for such a large global public good.

Olivier Hanotte, principal scientist

This article was published in the ILRI Corporate report 2016—2017. Download the full report here: http://hdl.handle.net/10568/92517

Partners: Bahir Dar University; Centre for Tropical Livestock Genetics and Health; Chonbuk National University; Georgia State University Institute for Biomedical Sciences; Kyungpook National University; Ministry of Livestock and Animal Production, Guinea; National Institute of Animal Science, South Korea; Nelson Mandela African Institution of Science and Technology; Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh; Seoul National University; Shinshu University; University of Khartoum; University of Illinois; University of Nottingham

Investor: Rural Development Administration, South Korea