Livestock-enhanced diets in the first 1,000 days of life: Pathways to better futures in low-income countries

A new report was published this month on the value of ensuring consumption of meat, milk and eggs by infants up to two years of age and by expectant and new mothers in developing countries (the first 1,000 days). The report was published by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the Chatham House Centre on Global Health Security.

The following highlights of findings

of a joint ILRI-Chatham livestock-nutrition study

were presented at a side event at the

EAT Stockholm Food Forum

on 11 Jun 2018.

I believe all of us here share the goal of the EAT Foundation—

‘a global food system that delivers healthy food in a healthy planet’.To make agricultural production more ‘resource efficient’,

so that it produces more with less environmental cost,

and to adjust the diets of the world’s food consumers,

so that they are neither over- nor under-consuming livestock foods,

are two sides of one coin needed to equitably as well as sustainably

nourish all the world’s peoples.My colleagues and I are concerned that well-meaning agendas

to reduce the negative environmental impacts from animal agriculture

will lead to undernourished people ‘falling between the cracks’.

Some of you may have seen this recent article in The Guardian presenting a worrying reality. Many research studies, and most recently a Science paper that The Guardian article quoted, demonstrate that agriculture, and in particular livestock production, makes big use of natural resource—including land, nutrients and water—at times with negative environmental impacts and with greenhouse gas emissions a prime focus of public concern.

This has prompted calls to reduce demand for livestock-source foods globally as a way to reduce such negative impacts. Chatham House has been active in this arena, producing, for example, influential reports investigating links between diet choices and climate change.

This recommendation speaks a lot to me, and I am sure to many of you in this room, who have many food choices and access to diverse, affordable and nutritionally rich foods.

Unfortunately, the world doesn’t look like Stockholm everywhere. There is another world out there where many people, and especially the poorest, consume none or very small amounts of livestock-derived foods to meet their nutritional needs and who have very few choices, or no choices at all, about what foods they do eat.

In this ‘other world’—where children rarely eat milk, or meat or eggs or fish and do not have diverse diets—child stunting is common, with its lifelong consequences on physical and intellectual development. In this other world, women who are pregnant or breastfeeding and have infants to feed struggle to meet the basic energy and nutrient requirements of themselves and their children with the foods available to them, which increases their vulnerability to illness and untimely death.

It is this other world that I am talking about today. I refer specifically to the next generation in low- and middle-income countries, and to how we can protect the future of that coming generation, to help it grow to achieve its full potential.

Global livestock production is one of many sustainability challenges that we face today, but before advocating that the whole world stops eating meat, milk and eggs, we should ask ourselves the following questions:

In poor households of developing countries, are livestock-derived foods needed in the first 1,000 days of life? Can livestock production improve nutritional outcomes in the children of these families? What would be the negative impacts of such consumption?

This is what drove extensive research by ILRI and Chatham House scientists on the role that livestock-derived foods can play in improving nutrition in the first 1,000 days of life—from conception through pregnancy, breastfeeding and up to two years of age. The results of this research were published earlier this month. Our aim was to generate evidence-based recommendations supporting the nutritional needs of children over this particularly vulnerable period of time in their lives.

While there is increasing evidence that over-consumption of livestock-derived foods is associated with an increased risk of non-communicable diseases, and while meat, milk and eggs, like many vegetables and other highly perishable foods, are known to be common vehicles for foodborne disease, there is also increasing evidence that livestock-derived foods can make important contributions to human nutrition and health, especially in the early years of an individual’s life and especially where diets are poor and lack diversity.

The scientific evidence in this area remains scarce, however. Virtually no data exist on the nutritional outcomes in babies of their pregnant and lactating mothers consuming livestock-derived foods. And there is a dearth of information on such consumption by infants in their first two years. But the evidence available suggests that the nutritional benefits of livestock-derived foods include the following.

- Milk supports child growth and may provide greater benefits in nutritionally worse-off communities.

- Meat can improve outcomes in a child’s cognitive development.

- Eggs: a recent research study showed that a supplement of just one egg a day almost halved stunting, a low-height-for-age condition associated with impaired physical and cognitive development, in babies in Ecuador while also supplying them with nutrients associated with cognitive development.

So, in crude shorthand:

If you want to grow tall, drink milk.

If you want to grow smart, eat meat.

And if you want to grow both tall and smart, eat eggs.

Despite the limited evidence available, it is unsurprising that livestock-derived foods can significantly improve nutrition, given their clear nutritional properties.

Livestock-derived foods are the most important food sources of Vitamin B12 (needed for brain development), have good micronutrient profiles (eggs are particularly rich in many nutrients), and possess high concentrations and high bioavailability of iron, zinc and Vitamin A.

See above, for example, that to meet her daily iron needs, a woman would have to eat eight times more spinach than cooked cow’s liver. Furthermore, because the iron present in spinach is bound to fibre, it is less bioavailable than that in liver.

Livestock-derived foods, which in addition to micronutrients contain essential amino acids and proteins, have great potential to help meet—in highly efficient ways—the higher nutrition requirements of pregnant and breastfeeding women and their infants. And although many foods other than livestock-derived foods possess these and other nutrients, such diverse foodstuffs are often unavailable, unaffordable or inaccessible by the poor.

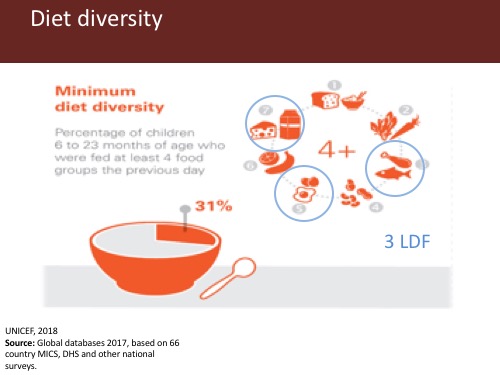

One further reason that makes livestock-derived foods particularly beneficial to diets is their contribution to diet diversity. A widely recommended indicator of infant diet is dietary diversity. A healthy diet is a diverse diet.

Dietary diversity in turn serves as a proxy for micronutrient adequacy. The more varied an individual’s diet, the more likely it is to meet that individual’s nutrient requirements.

The minimum acceptable dietary diversity includes four food groups. The total number of food groups comprising individual dietary diversity is seven, three of which are livestock-derived foods. Including livestock-derived foods in diets thus efficiently increases diet diversity as well as micronutrient adequacy.

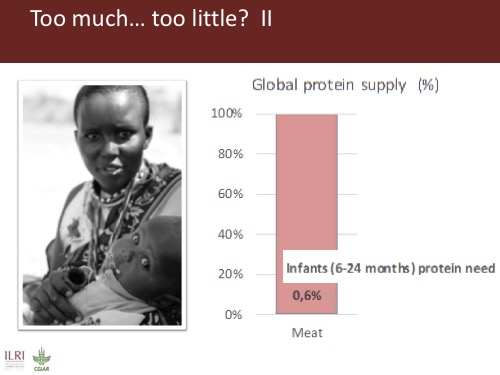

Just as there are lots of people in the world over eating livestock-derived foods, which has adverse health and environmental consequences, there are lots of people in the world eating none or small amounts of these foods. In 2013, meat, milk and eggs made up only about 20% of the total protein supply across Asia and sub-Saharan Africa but more than 50% in North America and Europe. And while the average per capita protein supply in the low-income regions was less than 15 grams per person, it was more than 50 grams in Europe.

The bottom line is that while there are many people who should decrease their consumption of meat, milk and eggs (and they will have to eat much less of these foods to reach the low levels consumed in most of Africa and Asia), there can be no argument to decrease even further the small amounts being eaten in many parts of the world.

Considering that livestock-derived foods can very efficiently enhance the diets of people otherwise consuming nutritionally poor and monotonous diets, and considering just how little livestock-derived food is needed to meet the protein needs of infants in their first 1,000 days of life (see the graph above), we should be able to ensure access to livestock-derived foods in those critical years, even if total global levels of livestock production are reduced.

So, if we agree that we can afford to do this, we need to think about how to do it—how to put livestock-derived foods on the plates of people who need them most in the most sustainable manner.

For many, the idea of promoting livestock production brings to mind images of animal-crowded intensive farming systems. But it’s important to remember that most people in low- and middle-income countries raise few rather than many animals and they don’t raise animals just, or even primarily, for food but rather for numerous and multifarious purposes, including the following:

- Converting grass and crop wastes into highly nourishing foods

- Recycling nutrients on mixed crop-and-livestock farms

- Providing draught animal power / traction

- Producing manure for fertilizing croplands

- Generating cash through sales of surplus stock

- Generating daily household incomes from sales of milk and eggs

- Providing insurance/resilience in the face of more variable climates

- Providing storage for capital reserves

- Fulfilling cultural/religious values/practices

In brief, raising farm animals in developing countries remains a major way to make a living—e.g., to be employed, to run a farm, to feed a family, to pay for medicines and education—where there are few other livelihood options. It’s also important to remember that environmental health comprises just one part of the ‘sustainability equation’; social and economic well-being are equally critical in building healthy systems and communities that will endure over time.

It is clear that—with cows, goats, sheep, pigs and poultry being ‘living assets’ that provide hundreds of millions of people with numerous sources of viable livelihoods, and better incomes in addition to nourishing foods—livestock in the world’s poorer countries are not going to disappear anytime soon.

But in many rural areas of the developing world where livestock are typically available, one in four children still do not have access to even the bare minimum of diet diversity. Just raising livestock is thus not enough to ensure better diets for the poor. Which in turn means that increasing the availability of livestock-derived foods is also not enough to ensure diet diversity. We must address issues of accessibility as well as availability. And at the same time, we must raise the levels of efficiency in smallholder livestock production systems so as to conserve the natural resources on which that production, and the environmental and climate health of the world, depends. ILRI research is directly addressing those livestock issues.

Considering that livestock are a central, prime and widely present asset in low- and middle-income countries, it would be irresponsible not to grab hold of opportunities to produce more meat, milk and eggs, and to produce these more efficiently, so that the millions of poor people consuming too little food of too little variety can begin to be nourished as well as simply fed.

And considering how little it would take to achieve this, it would be unethical not to protect those in their first 1,000 days of life with such nourishment.

So here’s a challenge for EAT—

Can we protect people as well as the planet? Can we acknowledge:(1) the important roles that meat, milk and eggs can play in the nutrition of the world’s undernourished poor and

(2) the challenges to making all livestock production systems more environmentally sustainable and

(3) the health problems of overconsuming meat, milk and eggs by those who can afford to do so?

And when it comes to global and national policies, can we align nutritional goals with sustainability goals with poverty reduction goals?

Our research showed two things that will be needed to bring this about. Nutrition scientists will need to become livestock-sensitive by paying greater attention to issues around livestock and livestock-derived foods, and livestock scientists will need to become nutrition-sensitive by paying greater attention to nutritional issues.

We are not going to meet the Sustainable Development Goals and achieve the 2030 Agenda if the nutrition and livestock worlds remain separate.

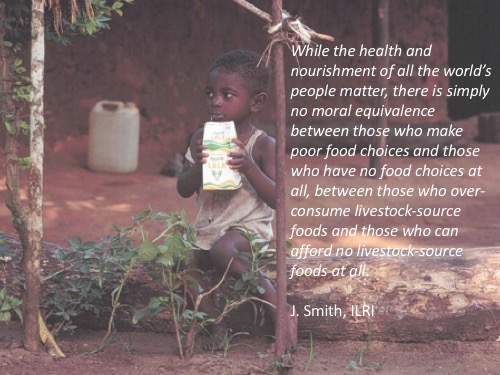

In conclusion, I ask us to consider that while public concerns about the human health and environmental risks of overproducing and overconsuming livestock-derived foods largely in high-income countries are legitimate, these legitimate concerns of relatively wealthy people should not serve to further limit the scarce nutritional choices of undernourished poorer people.

I ask us to remember the difference between making poor food choices and having no food choices at all. Between pathways to sustainable use of our planet that suit those of us here in Stockholm but that are impossible, even life-threatening, to those many others in other worlds.

I would argue that where it is both culturally appropriate and feasible, it would be irresponsible—indeed, unethical—to fail to utilize the world’s wealth of livestock resources to improve the diets of undernourished people, particularly of infants and new mothers.

I would argue that in our enthusiasm and commitment to save the planet, we have hard choices to make, but one of them, surely, is not to leave millions of people to fall between the cracks.

Ed: The notes that accompanied this slide presentation at the EAT Stockholm Forum were edited for the sake of clarity.

View/download the slide presentation by Silvia Alonso (ILRI), Mats Lannerstad (ILRI), Paula Dominguez-Salas (ILRI/LSHTM) and Nabila Shaikh (Chatham House): Livestock enhanced diets in the first 1,000 days: Pathways to healthy and sustainable futures in low-income countries? EAT Stockholm Forum, 11 Jun 2018.

Download the research report on which the presentation is based:

D Grace, P Dominguez-Salas, S Alonso, M Lannerstad, E Muunda, N Ngwili, A Omar, M Khan and E Otobo, 2018. The influence of livestock-derived foods on nutrition during the first 1,000 days of life. ILRI Research Report 44. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

Download a 4-page summary of the report:

D Grace, P Dominguez-Salas, S Alonso, M Lannerstad, E Muunda, N Ngwili, A Omar, M Khan and E Otobo, 2018. The influence of livestock-derived foods on nutrition during the first 1,000 days of life. ILRI Policy Brief 25. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

Read related news

Can livestock-enhanced diets of the poor in the first 1,000 days of life lead to healthy and sustainable futures? ILRI News blog, 7 Jun 2018.

Meat, milk, eggs can make a big difference in the first 1,000 days of life in low-income countries—New report, ILRI News blog, 4 Jun 2018.

Why milk, meat and eggs can make a big difference to the world’s most nutritionally vulnerable people, ILRI News blog, 4 Jun 2018.