Left to right: Albrecht Dürer, Studies on the Proportions of the Female Body, 1528; Franz Marc, The Shepherdess, 1912; Alexander Archipenko, Salome, 1910.

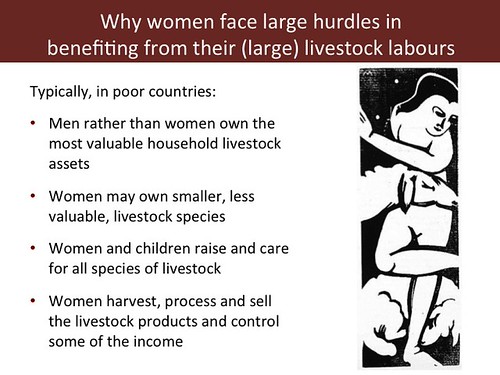

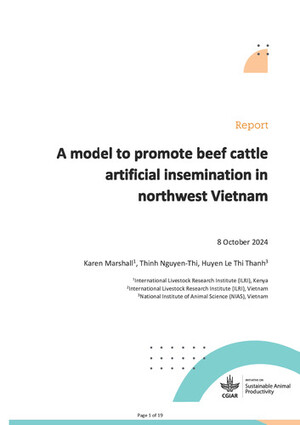

Women and livestock:

Why gender matters are BIG matters

View this whole ILRI presentation: Women and livestock: Why gender matters are big matters, 7 Mar 2014.

For more information:

Download Closing the gender gap in agriculture: A trainer’s manual, ILRI Manual 9, by Kathleen Colverson, ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya, 2013.

***

Capitalizing on women in livestock development

—ILRI’s Jimmy Smith and Isabelle Baltenweck speak out

Ethiopian woman holding one of her chickens (photo credit: ILRI/Apollo Habtamu).

Opening at the United Nations Headquarters, in New York City, today (10 Jul 2017) and running until 19 Jul is this year’s meeting of the United Nations High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development, convened under the auspices of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

This year for the first time the High-Level Political Forum is featuring events exploring the essential contributions of the livestock sector to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). ILRI Director General Jimmy Smith is at the UN this week to offer evidence-based insights into the close relationship between livestock and sustainable development.

The theme of this year’s forum is ‘Eradicating poverty and promoting prosperity in a changing world’. Four of the SDGs being reviewed in depth are:

- Goal 1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere

- Goal 2. End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture

- Goal 3. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

- Goal 5. Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

Throughout the week, the ILRI director general will speak on the ways livestock livelihoods in developing countries can help achieve these goals. About latter goal, Smith warns:

Because of the unique roles of livestock in women’s lives, we’re not going to achieve gender equity and empowerment of all women and girls (SDG5) without deliberate efforts to build upon the multiple and enabling roles that livestock play in female livelihoods worldwide.

—ILRI’s Jimmy Smith

A recent opinion piece on this subject was written by Isabelle Baltenweck, an agricultural economist and deputy leader of ILRI’s Policies, Institutions and Livelihoods program. Her piece was published by the Thomson Reuters Foundation News. What follows are some of Baltenweck’s key messages.

Ethiopian woman with the day’s eggs her chickens produced (photo credit: ILRI/Apollo Habtamu).

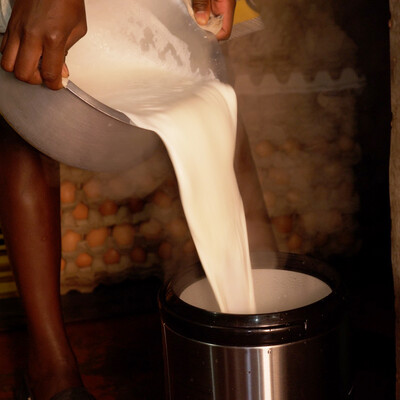

It’s a well-known adage that teaching a man to fish will feed him for a lifetime. But give a woman a cow, and she might still have to ask her husband’s permission to milk it.

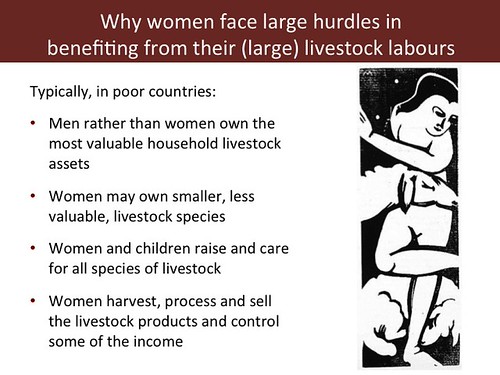

‘While women in developing countries assume much of the burden of raising household chickens, sheep and other farm animals, they receive relatively few of the benefits.

‘It is typically men rather than women who own the family stock as well as land, men who control the income that the animals generate, and men who have the better access to financial credit and new technologies.

‘The frequent exclusion of women from livestock ownership, resources and decision-making— an inequality that remains all-too-common in low- and middle-income countries—is a major factor in hindering households from escaping poverty.

‘But given the same resources and opportunities, women would be in position to equal men in transforming their family farms into profitable and environmentally sustainable enterprises. . . .

At the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), we call this a ‘WILD’ (‘Women In Livestock Development’) opportunity.

‘. . . And as women are typically closely involved in all aspects of animal husbandry—from feeding, milking and mating animals to caring for the young, sick or injured—technologies and resources that make livestock farming more efficient and productive should be made readily available to women. This might include market information, animal disease diagnostic kits and vaccines, land for planting fodder crops, and labour-saving chaff cutters for cutting up straw for feed. . . .

‘What we have then seen is that oftentimes, when women gain greater control over their livestock-derived incomes, the whole family benefits. This is because women in the developing world traditionally prioritise their spending on food for the household and education for their children. . . .

‘Tackling culturally embedded gender inequality is, of course, no simple task anywhere, and some would argue is a particularly complex issue among traditional livestock-keeping communities. But we know that livestock are among the most important assets of poor households, and among the most potent instruments of development. And we know that, given adequate resources, women can be formidable engineers of—as well as entrepreneurs in—livestock-based development.

If teaching a man to fish will feed him for a lifetime, imagine what enabling a woman to profit fully from her livestock enterprises would do: it could feed whole families, communities and nations—for a lifetime. . . .

—ILRI’s Isabelle Baltenweck

Read the whole opinion piece by ILRI’s Isabelle Baltenweck on the website of the Thomson Reuters Foundation News: Capitalising on the potential of women in livestock development, 6 Jul 2017.

***

The Women’s Empowerment in Livestock Index:

Indicators for the start of a global,

badly needed, conversation

Tanzanian farmer with her flock of chickens (photo by BRAC via Global Giving). The Women’s Empowerment in Livestock Index, piloted by ILRI in Tanzania, assesses the empowerment of women in production systems in which livestock are important.

Empowering women has been an implicit and explicit goal in sustainable development for decades. Full gender equality was made one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in Sep 2015.

The case for focusing on women is as much about efficacy as equity: Not only are women, and rural women in particular, deprived relative to men, but helping them sets the next generation on the right foot, as women generally place greater emphasis than men on the nutritional and educational needs of their children. But whereas measuring progress towards meeting some of the Sustainable Development Goals is fairly straightforward, women’s empowerment is a relatively complex and amorphous goal, bound up, for example, in a variety of domains and indicators that are context specific, and in individual empowerment pathways that are difficult to generalize.

To address these challenges, the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) developed in 2012 a Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI). This index has been refined over the years but still focuses mostly on women’s contribution to crop production decisions and activities. Recently, a team of scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), led by anthropologist Alessandra Galiè and in collaboration with Emory University, developed the Women’s Empowerment in Livestock Index (WELI), a new index to assess the empowerment of women in production systems in which livestock are important.

‘In many ways livestock provide opportunities for women’s empowerment that aren’t available in crop agriculture’, says Galiè. ‘Women in many poor countries can own chicken or goats, control the dispensation of milk and serve as gatekeepers for animal-based sources of nutrition. They can also take animals with them should they get divorced.’

At the same time, says Galiè, women in livestock consistently lag behind men on key indicators. They manage herds that are, on average, two thirds the size of those managed by men, they control less valuable species (mostly poultry while men control cattle), they are more commercially oriented but earn less than men, and they are less likely to use key inputs, such as labour, fodder and vaccinations.

Empowering rural livestock women improves gender equality and livestock livelihoods both.

Galiè and her team published the pilot findings of WELI last month as the lead article in Social Indicators Research. The paper focuses on six dimensions of empowerment, including women’s: (1) decisions about agricultural production, (2) decisions related to nutrition, (3) access to and control over resources, (4) control and use of income, (5) access to and control of opportunities and (6) workload and control over their own time.

‘Developing the index was a long, iterative and interactive process’, says Galiè. ‘For example, we first explored qualitatively the local meanings of empowerment in some communities of Tanzania. We then combined this information with standardized domains and indicators of empowerment (such as those of the WEAI) to develop the WELI tool. After piloting the WELI in Tanzania we did a second round of qualitative research to provide details on the “hows” and “whys” of empowerment that the WELI had assessed quantitatively. It was interesting to notice that the quantitative and qualitative findings diverged in some respects (a paper on this issue is currently being published). How to reconcile the fact that going to markets indicates high levels of empowerment in the WELI while in some communities going to markets is a low-status activity: the better off women become, the less likely they are to attend markets themselves.”

I asked Galiè why, given the complexity of an issue like women’s empowerment, it is important to try to boil it down to a single figure. ‘Partly it’s because quantifying a phenomenon allows scientists to measure its changes over time. An index provides a common framework or reference point to determine the effectiveness of various interventions. The ability to measure progress is important for policymakers who are accountable for the investments they make. Measuring changes in empowerment therefore can help support the integration of empowerment in development policies and programs. The challenge we are still facing, however, is to develop a methodology that measures empowerment while taking into account the complexity of empowerment processes.’

But it is not just the scientists who benefit from the elaboration of the index and the complementary qualitative work, Galiè told me. ‘Not infrequently, the women I and other fieldworkers interviewed would tell us that the experience of discussing these issues in depth had been illuminating and empowering for them. It helped them better articulate what their priorities and concerns are.’ In the future, we want to expand the potential of our methodologies to facilitate conversations about empowerment.’

Much of the original research in developing the index was done with dairy smallholders in four districts of northern Tanzania. Preparations are under way by another CGIAR research institute, the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), to extend the research to Honduras.

‘Eventually, says Galiè, we are hoping this tool establishes the basis for a global conversation about the kinds of interventions that work best on behalf of women in livestock around the world. At the same time,

. . . we are well aware that no mechanistic application of the index will be able to capture the complexity of women’s lived experiences, so we want this to be a start—and not the end point—of that conversation.

Download the Women’s Empowerment in Livestock Index article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amber Peterman, Peter Willadsen and Sophie Theis for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this paper. We thank all donors that have globally supported our work through their contributions to the CGIAR system, in particular the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Irish Aid and the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock and Fish.

***

When ‘Do no harm’ is harder than ‘Doing good’

This drawing depicts a traditional ololili dry-season forage reserve maintained by Tanzania’s pastoral Maasai communities, with images of a Maasai kraal homestead (upper left) and communal herding (upper right) (illustration from Ch. 14 of A Different Kettle of Fish? Gender Integration in Livestock and Fish Research, edited by R Pyburn and A van Eerdewijk, LM Publishers, Volendam, 2016).

Written by ILRI social scientist Alessandra Galiè.

Agricultural researchers working to enhance traditional pasture conservation by Tanzania’s pastoral Maasai communities are systematically addressing gendered norms and roles to ensure that they don’t end up hurting more than helping these communities.

Across the rangelands of Tanzania, pastoral communities rely on their livestock for food security. During the annual dry season in particular, animals produce the milk that feeds the family when little other food is available. Yet feeding animal herds in this season is hard work. During these four to five months, the men move away, taking most of the household animals with them in search of fresh pasture, leaving behind only a few animals that the women will rely on to feed themselves and their children until the men (and the rains) return, months later. The animals that are left behind in the homestead are typically stock unlikely to survive the journey to and from the grazing grounds because they are pregnant, lactating, sick or injured.

Maasai have relied on a traditional Maasai pasture conservation system to feed their animals. In this system, known as ololili in Maasai, a single household, or sometimes several households working together, will fence a bit of land with thorny branches and bushes. Inside these enclosures, the natural pasture, composed of wild plants, is left to grow undisturbed during the wet season. Then, during the long dry season, when pasture grasses are spent, the women let the vulnerable stock left in the homestead by the men into the ololili to graze on the reserved green fodder for several hours a day. A typical single-family ololili of about 0.8 hectares (nearly 2 acres) is sufficient to support 5–6 cows and 2 calves throughout the dry season. With the men away, it is the women who control access by the animals to the ololili enclosures, ensuring that the animals are sufficiently fed but do not overgraze the area.

Forage scientists working with Maasai communities in eastern Tanzania consider this traditional pasture conservation system to have great potential to support food security during the dry season. By increasing the number of plants growing in the ololili scientists would support an increase in the amount of forage available to pastoral animals. Such forage intensification would enhance food security here by making more milk available to households during these yearly ‘lean seasons’. The benefits of such an intervention could be particularly big here, they reasoned, where severe dry-season forage shortages drastically reduce milk supplies every year, with animals and people alike commonly losing weight, children commonly pulled out of school for lack of fees, and cattle, goats, sheep and even camels commonly dying of hunger.

To intensify the ololili forage system, the researchers aimed to introduce plant varieties suited not only to the local rangeland conditions but also to the local social, economic and cultural systems. The researchers, Alessandra Galiè and Ben Lukuyu, who come from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and Walter Mangesho and Jonas Kizima, from the Tanzania Livestock Research Institute (TALIRI), quickly began to see that to be successful, they would have to pay close attention to the different roles that women and men play in managing the ololili system.

In 2015, we began to work with a group of ILRI scientists to investigate gender issues around ololili and general livestock management in Maasai households in Tanzania’s Morogoro region. We looked specifically at the types of forage grasses, shrubs and trees preferred by members of the community and at the opportunities and the constraints faced by women and men in managing the ololili dry-season forage reserves. The findings from this gender study informed our selection of plant species and varieties to introduce to intensify forage growth. Importantly, the findings informed institutional as well as technical interventions, with the former focused explicitly on determining ways to best ensure that both women and men actively participated in, and benefited from, this forage conservation project.

The ololili-related roles in these Maasai households are gendered. Men do most of the livestock breeding work, as well as sourcing animal and human medicines and moving their herds to dry-season grazing grounds for several months each year. Men also are responsible for claiming the pieces of land within the community that they will fence off for their family’s ololili reserves and for building and maintaining the rough thorn fences. Women are in charge of feeding animals that stay in the homestead, managing the ololili and its use while the men are away, milking the animals and selling any milk, identifying animal diseases and looking after sick animals, and feeding their families.

These discrete roles of men and women were found to affect their preferences for traits of the wild forage plants in their ololili. Women, for example, prioritized plants that increased milk productivity because they controlled all aspects of milk production, sales and consumption. Men, on the other hand, ranked high those plants that are good for human medicinal uses because of men’s role in procuring medicines for household members. Understanding these gendered trait preferences turned out to be critical for choosing what plant species and varieties to introduce to intensify ololili forage production. In the end, the TALIRI and ILRI scientists were able to identify two plant species that possessed two traits that men and women both preferred: an ability to tolerate drought and to increase the milk productivity of the animals.

The gender study also revealed customary norms affecting the ways women performed their household roles. For example, because men are considered the sole decision-makers in household matters, women had little say as to how to manage the ololili or which animals should be left behind at the homestead during the dry season. Women reported that this lack of decision-making hurt their ability to feed their families, as they are the ones tasked with feeding their families in the annual ‘hunger months’ and must do so with no support from the men who are away and with the little milk produced by the needy and unproductive animals the men choose to leave behind.

This community’s customs also discourage women from speaking in public and from interacting with men who are unrelated to them. These norms prevented women, widows and single women in particular, from claiming land to build an ololili and therefore from establishing a forage reserve. The norms also discouraged women from facing up to men who let their animals invade the women’s ololili to consume their precious conserved grasses. Once depleted of forage, of course, an ololili is of no further use for another whole year, until after the forage plants have grown again in the next rainy season.

We considered addressing these and other constraints faced by these women essential to the success and sustainability of our technical forage interventions.

We saw, for example, that if the project managed to increase and improve the biomass grown in a given ololili but paid little to no attention to gender issues, such forage intensification might serve only to make that ololili even more attractive to male invaders, leading to greater, not lesser, food insecurity in the households adopting the forage intervention.

Our project would thus inadvertently end up hurting the food security of the very households we were aiming to help.

Based on these findings and understandings, we began initiating ways to help increase the profile of the women and their decision-making regarding the ololili system while at the same time ensuring that men were actively involved and benefited as much as women from the project. To address gendered norms likely to reduce the usefulness of intensifying the ololili system for better food security, we involved from the very start of the project women and men equally in selecting and planting improved pasture plants. We also conducted a ‘forage champion’ initiative to give higher visibility to the roles women play as ololili and livestock managers with the aim of supporting an increase in women’s decision-making.

We noticed that simply having conversations on gender roles in the household helped household members to acknowledge their complementary contributions to household food security and also helped women to find their voices regarding ways they could further improve their contributions. Today, we are continuing to develop and implement strategies aiming to gradually create a social environment more conducive to inclusive and sustainable management of ololili for the betterment of whole households. We are also attending now to finer-resolution social characteristics, such as the marital status, age and wealth of the women, that are likely to affect the gender dynamics—and thus the success or failure—of our forage improvement interventions. The constraints faced by widows and single women, for example, may need to be specifically addressed to ensure the success of the intervention.

An important learning for us was that agricultural researchers need to take explicit, systematic and expert approaches to address gender issues as well as, say, to agroecological, technological and policy issues. If no gender approaches are included, or if those included are not explicit, systematic and expert, we found that we were likely to miss gender-specific factors critical to the success of our technological intervention.

The sticky part is that it takes a lot of conscious effort and committed time to modify traditional gender norms.

Like many other development experts, we agricultural scientists can easily find ourselves unthinkingly accepting gendered roles, and so end up reinforcing the very behaviours that can sabotage the success of our interventions.

In our particular case, a failure of ours at times to maintain explicit considerations of gender issues in all stages of our forage work had us easily slipping back into taking ‘gender-blind’ approaches that might, if continued, have propped up existing gender norms and so derailed our project.

Our ultimate aim in this project was to ‘do good’. We aimed to help pastoral Maasai households get through the annual dry season without going hungry, losing their stock or descending into severe poverty. But we learned that ‘doing good’ through forage technology is the easy part. We learned that ‘Do no harm’ is the harder part. We learned that we’re simply not going to succeed in our forage work if we fail to succeed in our gender work.

For more information, contact Alessandra Galiè at a.galie [at] cgiar.org.

See also Getting by in the dry season: Ololilis in Tanzania, by Alessandra Galiè and Ben Lukuyu, chapter 14 in Rhiannon Pyburn and Anouka van Eerdewijk (eds), A Different Kettle of Fish? Gender Integration in Livestock and Fish Research, LM Publishers, Volendam, 2016.

Acknowledgments

The initial technical research on establishment of improved forages in the ololili system in Tanzania was undertaken as part of a MilkIT project (Enhancing dairy-based livelihoods in India and Tanzania through feed innovation and value chain development approaches), which ran in Tanzania and India from 2011 to 2014 and was funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The project was led by ILRI. The International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) was responsible for activities in Tanzania.

***

‘Wonder Women’ of Bhubaneswar

Temple carving in Bhubaneswar (this and all photos on this page by ILRI/Susan MacMillan).

8 Mar 2016: 5:30 am

My communications colleague at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) Jules Mateo and I are in the lobby of our hotel in New Delhi checking out. I’m groggy, having been up all night catching up on emails and finalizing a blog article to celebrate ‘women in livestock development’ (aka, WILD) on this day, which happens to be International Women’s Day. I’m a few minutes late getting down to the lobby to check out.

A taxi waits to take us to the airport for our early morning flight to Bhubaneswar, capital of India’s eastern state of Odisha (formerly, and still commonly, known as ‘Orissa’). On arriving at the Delhi airport and quickly entering, we find we’re in time for our flight but I’m still relieved when two women from Air Vistara, the newish domestic airline we’re using, approach us to ask us to move a new queue. I assume our check-in is being expedited.

But no, that’s not what’s happening. What’s happening is that we’re both being bumped up to business class. It turns out that Air Vistara (‘vistaar’ means ‘limitless expanse’ in Sanskrit) is making a big effort to celebrate International Women’s Day, and Jules and I have just been selected to receive some special treatment. This felicitous pre-dawn airport incident will turn out to be just the first of many day-long occasions marking this special day in India.

Memento of the upgrade!

On receipt of our new business class tickets and boarding cards (stapled with festive yellow ribbons), we’re each handed a little bouquet of flowers. The airline women ask if we’d mind having our pictures taken with them (of course not!) and then we make our way, giddy with excitement about our unwarranted upgrade, to the gate. The whole airport appears to be conspiring in this celebration: the woman who pats us down at the security check, for instance, wishes us a ‘Happy International Women’s Day’, as do several others.

Boarding our plane, we’re directed to our comfy business class seats and offered a selection of the day’s morning papers and a freshly squeezed juice before take off. The stewardesses give us every possible attention on our (now too short) flight. (I spend most of the 1.5 hours catching up on my sleep and am sad to miss the elaborate Indian breakfast.)

As we land, our ever-attentive stewardesses ask if we’d mind staying behind as everyone else gets off the plane so that another series of pictures can be taken. This time the pilot comes back to join us in the selfies and other mobile snaps—and it turns out the pilot is another Indian woman. In fact, everyone handling this flight appears to be a woman, reminding me of the news splash the previous Nov about an all-female crew on an Ethiopian Air flight from Addis Ababa to Bangkok, with—the media reported breathlessly—‘the daughters of Lucy’ fully operating the journey, from ground to sky, on the eve of that airline’s 70th anniversary.

A delicate fact that I have as yet omitted to mention is that Jules and I are travelling with three of our superiors, our director general Jimmy Smith and his wife Charmaine as well as ILRI’s representative for South Asia, Alok Jha. Our embarrassment about travelling business as they sit back in coach, and about getting so much attention from everyone all morning, becomes a joke as Braja Swain, an ILRI scientist and project leader in this state, packs us all into a vehicle to take us to the Bhubaneswar hotel where Jules and I will be staying that night.

As the joke continues on our way from the airport, we pass billboard signs promoting International Women’s Day (the whole country has been infected!). This reminds Jha that he once spent a few months working for an institute in Bhubaneswar that solely serves women farmers, the only such institute in all of Asia, he says.

8:30 am

Alok Jha gets out his cell phone and puts a call in to a colleague he still knows there, suggesting that as our ILRI delegation is in town for the day, we could pay a visit to the institute that afternoon, at their convenience. Jha’s call is transferred to the head of this institute, who immediately extends us a warm invitation for us to visit her after lunch.

Scenes of our series of morning courtesy calls on government and university VIPs in Bhubaneswar.

10:00 am

Which is what—following a morning spent making courtesy calls on various senior government officials and university professors to discuss livestock research collaborations—we do.

Memento of some of the VIPs the ILRI delegation visited in Bhubaneswar.

Poster advertising celebrations at Bhubaneswar’s Central Institute for Women in Agriculture to mark International Women’s Day.

2:00 pm

The Central Institute for Women in Agriculture belongs to the vast network that makes up the Indian Council for Agricultural Research. As we enter the large building housing the institute, we’re immediately shown to the director’s office. Jatinder Kishtwaria is waiting for us and serves us chai and an assortment of India’s milk-based sweets. We introduce ourselves and enquire about her institute’s programs, which, she explains, she herself is just getting to know as she took up her position just 20 days previously. After 20 minutes or so, we thank her and begin to make polite noises about taking our leave.

As our host walks us out her door, we catch something she says about a ‘program’. We dutifully follow her down a hallway and enter a large conference room filled with people seated, where, it quickly transpires, the senior members of our little delegation have been made honoured guests at an event about to start. The Smiths and Alok Jha are handed bouquets of flowers and shown to their seats on the raised dais at the front, along with the other speakers on what, we now understand, is a whole afternoon’s program marking International Women’s Day.

Jimmy Smith, Alok Jha and Charmaine Smith all made impromptu speeches at an event held on 8 Mar 2016 celebrating International Women’s Day at the Central Institute for Women in Agriculture, in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India.

The afternoon’s proceedings could not have been more delightful, nor we more delighted to be taking part. Jimmy Smith, Alok Jha and Charmaine Smith each gave a little impromptu speech (Jha noting that ‘Every day should be International Women’s Day!’). One of the women who spoke received an award for her agricultural entrepreneurship. Several staff of the institute recounted the history of women in Indian agriculture, what the institute had achieved in working for them, and how far the world had advanced in helping agricultural women advance. And how much remained to be done.

At the close of the program, we leave the conference room to take chai, consumed with a box of milk sweets, while chatting with the other guests and taking in several special exhibits and poster displays.

(Top) Nehru quote hung above an office door at CIWA; (bottom left) Jatinder Kishtwariathe, director of CIWA, reflects on the day with ILRI’s Charmaine Smith; (top right) two of the many women guests at the event; (centre right), the CIWA staff member who was master of ceremonies at the event; (bottom right) the woman bestowed an award for her agricultural entrepreneurship .

Among the exhibits set up were several tables displaying small replicas of agricultural implements designed to reduce the labour or danger of farm work traditionally done by women in India. While inspiring to see that such improvements are being made, and that the prices of the tools are subsidized by the government to make them more affordable by poor women, it also broke the heart a bit to see how rudimentary are the advances and how heavy remains the menial load and drudgery work of India’s hundreds of millions of farm women.

As Nehru so rightly indicated, it is the women of India who, once on the move, will get the nation moving. Certainly, we met some of these ‘Wonder Women’ of Bhubaneswar on this auspicious day.

With many thanks to Jatinder Kishtwaria and her colleagues at ICAR’s Central Institute for Women in Agriculturefor the great work they are doing and for their inspiring afternoon’s event.