Viral flash points? Poor urban settlements are highly vulnerable to the risk of the new coronavirus

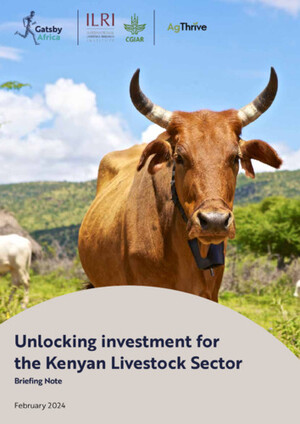

Scene in Nairobi’s low-income Kibera settlement (photo credit: David Orgel/Flickr).

A new guest blog article published yesterday (27 Feb 2020) on the website of the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) argues that:

Weak infrastructure would leave urban settlements in low-income countries highly vulnerable should the rapid spread of COVID-19 continue

The following is excerpted from the guest blog article, which was co-written by Eric Fèvre, a veterinary epidemiologist who is a joint appointee as principal scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and chair of veterinary infectious diseases at the Institute of Infection and Global Health (IGH) at the University of Liverpool, and Cecilia Tacoli, principal researcher in the Human Settlements research group at IIED.

‘. . . So far, COVID-19 has been reported in only high- and middle-income nations where effective health systems are in place, and conditions are generally sanitary. But what will happen if the disease spreads to cities in low-income nations?

‘Many low-income settlements lack basic infrastructure and services. Unsafe water, inadequate sanitation, open drainage and refuse dumps are all factors attracting rodents and other parasites. These are prime reasons for the high prevalence of infectious diseases.

‘In crowded spaces, people are forced to share accommodation and—when available—toilets.

- Residents are constantly on the move, often traveling on packed mini-buses—to workplaces within settlements, between settlements, between the city and rural homes. Attempting to control this kind of movement would be extremely difficult.

- For example, current recommendations for preventing the spread of the disease include washing hands frequently—but this is extremely difficult where clean water access is limited.

- Isolation is another recommendation—but this is almost impossible to put into practice in settlements where population density is extremely high. Self-quarantining—staying at home for at least 14 days—is scarcely an option for the urban poor who often rely on daily wages from casual labour.

‘Short-term efforts are focused on containing the spread of infection. The longer term—given that new infectious diseases will likely continue to spread rapidly into and within cities—calls for an overhaul of current approaches to urban planning and development.

‘Low-income settlements need more effective infrastructure. Often labelled by city authorities as “informal” or “illegal”, these settlements do not receive investment for basic services such as piped water, sanitation or electricity. They are not served by primary healthcare facilities or regular solid waste collection. And yet these settlements often house over half of a city’s population, being the only affordable option for many residents.’

Recognising the existence of affordable (though grossly inadequate) forms of housing that in effect subsidise labour costs for the rest of the city’s inhabitants is a first step not only towards addressing the challenging living conditions of low-income settlements, but as a way of helping contain the spread of new and deadly contagious disease.

Read the whole article, Coronavirus threat looms large for low-income cities, by Eric Fevré and Cecilia Tacoli, on the IIED website, 26 Feb 2020.