A soil safari: on a quest to restore and manage grassland soils

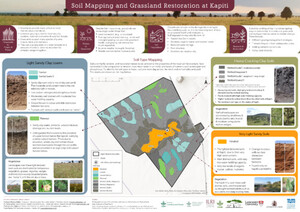

As we jumped up and down on the bumpy roads at Kapiti Research Station and Wildlife Conservancy, our team was on a quest to map the different soil types across the conservancy. We were headed on what we coined a 'soil safari.'

Amidst seeing herds of zebras and giraffes the team, led by new doctoral candidate Fiona Pearce and accompanied by professors John Quinton and Nick Ostle from the University of Lancaster (LU), UK, jumped out of the car every 10 minutes to assess the soil type. They are aiming to understand how the soil types change across the ranch, developing a soil map to inform research at Kapiti on soil and grassland health. Their overall mission: to understand how we can effectively restore and manage degraded grassland soils in southern Kenya.

Kenyan grasslands are under increasing pressure from extreme weather such as drought and flooding, invasive species, and poor management like overgrazing. This can cause degradation of the soils beneath, depleting them of nutrients, carbon and life; damaging their structure (e.g. through compaction), and in severe cases causing topsoil to be lost completely through soil erosion. Soil degradation can have long term effects on grassland productivity and resilience.

‘There has been a lot of research on intensively managed grasslands in Europe and the USA, but less on tropical grasslands in semi-arid areas of east Africa. Research has also tended to focus on aboveground communities (plants) and neglect the important role of healthy soils in supporting healthy grassland ecosystems.

We still don’t have a good understanding of how the soils underlying Kenyan grasslands, which are different to soils in temperate regions, might respond to different management or restoration interventions,’ said Pearce.

Conducting research to improve soil health

Understanding the importance of soils in land management decisions and policymaking is crucial in creating resilient food systems and mitigating the effects of climate change. In her doctoral studies, Pearce is partnering with the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) where she will implement different interventions, such as re-seeding with different grassland species and adding organic material such as manure, to test how they affect grassland soil health.

Pearce is advised by John Quinton (LU), Mariana Rufino from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and Sonja Leitner (ILRI). Quinton and Rufino are also collaborating with the University of Kabianga in Kenya, and farmers and landowners in western Kenya. Lancaster University has set up a new Africa Research Hub dedicated to 'advancing academic research, fostering community engagement, and promoting sustainable development across the African continent' which will serve to further build the partnership between LU, TUM, ILRI and other Kenyan partners.

‘Soils can be a bit invisible, but if you’re degrading soils, it can take a long time to reverse the impact,’ said Leitner, who is a senior scientist at ILRI.

There is currently limited evidence for how different management strategies used in tropical grasslands like Kapiti's can impact these soils, and help them to become more resilient to climate changes such as drought. Pearce’s work is crucial to bridging this gap because understanding the role of soils for providing crucial ecosystem functions such as nutrient and carbon cycling can help increase productivity and improve drought resilience.

Pearce is testing intervention methods such as planting legumes to measure the effects on soils and vegetation, and assess whether they can increase resilience to drought. Legumes were chosen because they help fix nitrogen, a nutrient that savannah soils are typically low in, especially where they have been degraded by overgrazing or soil erosion.

Pearce’s visits to Kenya in May and December helped build her knowledge of Kapiti’s soils and Kenyan agriculture systems and skills including: soil classification and sampling, botanical surveys and plant identification, and taking measurements such as soil respiration.

As we embarked back to Nairobi, Pearce shared with me that she has taken the “scenic route” to starting her PhD, having worked for 10 years in environmental management the public and private sectors but finally finding herself drawn back to research.

‘Doing a PhD is a bit of a career pivot for me, and an amazing opportunity to spend 3 years learning about soils, Kenyan agricultural systems and savanna ecosystems, as well as gaining research skills from experimental design to fieldwork, lab analysis and grassland plant ID skills. I know it’s going to be hard work but it’s also going to be a great adventure and hopefully a lot of fun!’ said Pearce. ‘

In return, I’m hoping that my research will make a small contribution to our knowledge of how we can restore degraded soils, providing evidence to inform decision-making.’

May her curiosity and enthusiasm inspire other aspiring scientists to pursue soils and rangelands research. Building upon deeper understanding of grassland soils and discovering the best intervention methods will help semi-arid areas around Kenya like Kapiti stay resilient in the face of climate change.