One-size-fits-all ‘livestock less’ measures will not serve some one billion smallholder livestock farmers and herders

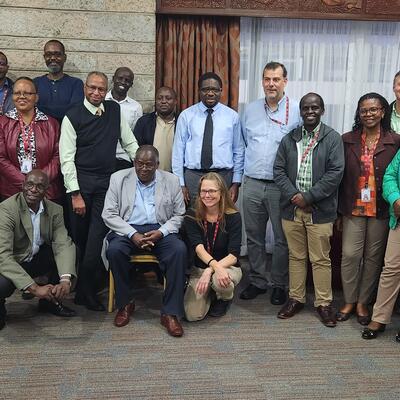

Smallholder dairying in Kenya (photo credit: Accelerated Value Chain Development/Sophie Mbugua).

‘Once again, the debate on sustainable diets and in particular on (not) eating animal-derived products is resurfacing in the media, as illustrated most recently by an article in The Guardian. The paper reported on a study by J. Poore and T. Nemecek entitled ‘Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers’, published in the latest edition of Science magazine. The article concludes that ‘avoiding meat and dairy products is the single biggest way to reduce your environmental impact on the planet’. Both the study and the article recognize the ‘large variability in environmental impact from different farms’ and the need to deal with the most harmful ones. Still, they seem to overlook the evidence from the 1.3 billion smallholder farmers and livestock keepers for whom livestock is an important source of income and food security.

Family goat keeping in India (photo credit: ILRI/Christoph Weber).

The vast majority of these smallholder farmers and livestock keepers produce meat and dairy in a sustainable way (socially, economically and environmentally friendly).

They make little use of external inputs such as fossil fuels, use manure to fertilize soils in integrated crop production and grow their own animal feed.

They therefore cause less greenhouse gas emissions related to transport, manure production and use of fertilizers.

Moreover, their production systems substantially benefits the environment, thanks to its many eco-system services for climate change mitigation and biodiversity increase.

‘The importance of livestock for smallholder famers goes far beyond the economic logic of certain types of industrial livestock keeping. It benefits crop production, as animals are used to work on the land and their manure to fertilize the soil. It has a clear economic and social value; farmers derive an income from selling milk and live animals, and livestock plays an important socio-cultural role in their lives, for instance as a wedding dowry. Livestock also contribute significantly to improved food security and nutrition. . . . A reasonable consumption of animal-derived products—produced locally and using sustainable farming practices—could improve their food security and nutrition substantially. Milk, for instance, is an excellent source of macronutrients, dietary energy, lipids and proteins of high nutritional quality. It also provides carbohydrates, calcium and vitamins. But the role of animal- derived products must also be recognized in fighting the so-called “hidden hunger” or micronutrient deficiency, which is affecting over 2 billion people worldwide. . . .

Household pig keeping in Vietnam (photo credit: ILRI/Chi Nguyen).

[I]n 2025, average meat consumption in the EU will attain about 70 kg per person per year.

In Africa—where a big part of the world’s smallholder livestock keepers live and where 22% of the population suffers from undernourishment—meat consumption will only attain 11.3 kg on average.

This clearly illustrates the important differences in worldwide meat consumption and the need to nuance the conclusions of this study according to the regions where they would apply.

‘Furthermore, within the 1.3 billion people depending on livestock for their livelihoods, we cannot forget the estimated 200 million (agro-)pastoralists. In arid and semi-arid lands, mountainous areas, non-arable land and natural rangelands, pastoralism is the only possible production system that allows to transform non-edible plants and marginal lands into nutritious food (meat and milk). These lands, which cover half of the world’s land surface, cannot be used in any other way for human consumption if not grazed by animals.

‘Rangelands have an enormous potential for carbon sequestration and pastoralists are key to maximizing this potential through their mobility. Well-managed pastoralism also provides important ecosystem services and co-benefits for people, including maintaining soil fertility, managing fires and regulating pests and diseases. Though pastoralism does produce methane, one could argue that ‘without the presence of domestic livestock, methane emission would probably remain stable and not be reduced since the pasture would either be burnt or eaten by wildlife or methane producing thermites’ . . . .

Pastoral herding in Tanzania (photo credit: KINNAPA/AbrahamAkilimali).

‘Therefore, the debate on production and consumption of animal-derived products should be set in a wider context, recognizing more explicitly the differences between production systems and stressing their diversity. While some systems are undeniably damaging for the environment and the welfare of the animals—as rightfully put in both the article and the research—others are pivotal for people’s livelihoods and contribute to environmental sustainability. In addition, a stronger focus should be put on the important role of sustainably produced animal-derived products in fighting hunger and chronic malnutrition.’

Conclusions based on societies marked by overconsumption of industrial animal products should not be transposed to countries where animal products are produced in a sustainable manner and where their consumption guarantees improved food security and nutrition.

Nuances are needed, and the perspective of these 1.3 billion people must increasingly be defended in international debates on animal production and consumption of animal-derived products.

Read the whole article: Avoiding meat and dairy: A one-size-fits-all measure to deal with our planet’s environmental problems or a real option for the 1.3 billion people depending on livestock to assure their livelihood and food security?, Vétérinaire Sans Frontières News, 12 Jun 2018.