Kenya: Meet the young entrepreneurs milking opportunity in the dairy sector

Posted on

by

- Georgina Smith

- Renee Bullock

Keeping livestock is a lifeline for hundreds of millions globally

Domesticated animals bring people nutritious meat, milk and eggs. They bring income when money is scarce and provide crop farmers with draught power. Livestock provide young people with jobs and other income opportunities

Measuring greenhouse gas emissions from cows at The Mazingira Centre at ILRI, an environmental research and educational facility

Can young people tap the growing opportunities of dairy intensification in Kenya and simultaneously curb harmful greenhouse gas emissions?

Back when Samuel Ndung’u needed a laptop to help him in his high school studies, he didn’t go to the bank. He didn’t get a loan, or ask his parents for money. Instead, he sold his first cow. Like more than a third of young Kenyans looking for job opportunities, Samuel, now 28, lives on his family farm, in his case a neat homestead owned by his grandmother and occupied by several generations in the country’s biggest milk-producing county, Kiambu, on the outskirts of the Kenyan capital, Nairobi.

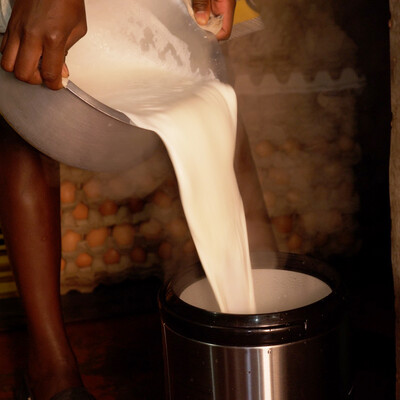

Samuel’s day, every day, starts at 5 am. He milks his grandmother’s cow and two of his own cows, fills and drops off aluminium milk cans at the bustling milk collection depot and then goes back home to make milky sweet tea for the family. He chops up feed for the cows and feeds the chickens.

On average, Samuel delivers 35 litres of milk a day to nearby cooperatives, making a profit of USD 200 during peak dairy seasons. Milk and eggs provide for his family’s daily meals. In the afternoon, he sets aside time to build a new cowshed and what will eventually be a small house for himself, on land allocated to him by his grandmother near the family house.

It wasn’t always like this. In an earlier stint working as a sales assistant in Kiambu, Samuel put in late-night shifts of 14 hours or longer. Earning a basic salary of USD 73 a month, with long periods away from his family, he had a career re-think.

Like thousands of other young Kenyans, Samuel decided to become a dairy entrepreneur instead. Dairy is a big opportunity in Kenya. Kenya’s cows produce over 3.5 billion litres of milk a year. Kenyans consume more milk than people in any other country in Africa, and the demand for dairy products is on the rise. By 2030, Kenya is likely to become a net dairy exporter.

Tapping into the country’s large and growing dairy opportunities, Samuel now makes more money than ever before, and while looking after his cows every morning and afternoon, has time to do other things.

‘Imagine how many people in this country drink milky tea every morning and every afternoon’, he says, making his way through his small plot, carrying a handful of forage for his cows. ‘All those people need milk. That is a lot of milk. For young people like me, who start out with nothing, that is a great opportunity.’

Samuel’s semi-urban farm setting helps. His grandmother’s lush green farm is near dairy cooperatives that buy their daily milk, good roads, electricity infrastructure and water supplies.

After feeding his cows, Samuel takes off his boots at the kitchen door and lights the stove for morning tea. The gas, he explains with a grin on his face, comes from a biogas digester he fitted in the garden, where bacteria break down excrement from his cows. He bought it with the money he made from selling two cows, which he named ‘Gas’ and ‘Cooker’.

Every morning, after cleaning out the cowshed, he mixes the cow manure and urine into the biogas filter with his hands. ‘Some people say you stink after doing this work’, he says. ‘This heats up my water for bathing, so I don’t mind.’

But Samuel faces crippling threats, too. With limited control over the animals, which belong to himself and his grandmother, he doesn’t own land and has little money to invest. He has ‘side-hustles’, like repairing computers. But he still depends on his family, who for the most part have supported him morally and financially.

‘Sometimes people fear change’, he says, reflecting on the cynicism he faced when he asked for money to invest in the biogas digestor. ‘[My family] wondered if this would add up. Now everybody enjoys [going] into the house, lighting a match and having fire to make tea and cook with.’

Not everyone is so lucky to have Samuel’s family support. A four-hour drive away, in the hilltop town of Nakuru, 31-year-old Lilian Satia starts her day. She knows Samuel through a workshop, but their lives are very different.

Lilian is a wife and mother of three. At 5am, she wakes up to make breakfast and get her children ready for school. She cooks, cleans and manages the house. As dawn breaks, she heads down a tarmac road in thick morning mist to a local milk bar.

Reaching the milk bar—a small shop with blue doors serving as both a milk collection and sales point for dairy farmers and a shop for customers to buy milk—she swings open the window in the wall, revealing a hive of activity. Bicyclists ride up to drop off aluminium milk cans while a small queue of customers forms.

Deftly pouring a fresh ladle of milk into a bottle for a customer at the hatch, she explains why she and nine other young people started the initiative, which is part of a larger cooperative. ‘Women do suffer a lot. All the work belongs to women here. But the money belongs to men’, she says.

Typically in smallholder Kenyan dairy farming, men keep the money made from selling the morning milk and women get the evening milk money—about half that of the morning sales, she explains. ‘[Milk] prices were not so good in the past and people [were] not paying us for the milk they bought.’

Lilian and a group of nine other youth founded the milk bar as part of a youth group initiative supported in part by a Smallholder Dairy Commercialization Programme of the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

‘We came up with the idea of a milk bar. We started delivering our own milk; then the demand began to rise. The milk bar has been a way to keep control of our income. I know when customers pay and how much’, she says.

Lilian knows she is going against cultural expectations by becoming a ‘milk entrepreneur’. Most women in this area don’t own cows or make decisions about the income their household’s cows generate. But while farming may be considered ‘dirty’ work by some, it has provided her with welcome income, in an area where jobs are few.

© Georgina Smith

Stirring a pot of beans and carrots, as smoke drifts around the kitchen, Lilian explains that she is well aware of the cultural hurdles she is up against as both a young person and a woman. Things were not that different for her 67-year-old mother-in-law, Serah Nganga, who lives next door and helps Lilian occasionally with preparing food for the evening meal.

Serah runs a kiosk selling sweet-smelling mandazis (donuts), soap, flour, potatoes and other basic goods. Arranging some boxes on a shelf, she rests thoughtfully against the shop counter and reflects on her experience.

Cooking, fetching firewood, making open fires for cooking and breathing in smoke fumes, working hard both in the home and on the farm—‘Women are the pillars of the household’, she says. ‘It’s hard work.’

Back on the farm, Lilian disappears into the kitchen and emerges with rosemary-infused tea. Setting it down under the shade of a tree, she chats with a visitor—Lydia Kimachas—an extension worker from the Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries’ Department of Livestock Production.

Lydia is passionate about supporting young people like Lilian and Samuel in their ventures. But she knows they need the right kind of support to thrive.

‘For youth, one of the main challenges I see is lack of ownership of land and animals. They often have access to land, but if they don’t have ownership, they can’t make decisions about what to do with the land and the cows. And they can’t afford to buy their own assets.’

‘I’d like to see more [youth] involved in agriculture and more successful’, she says, watching Lilian as she dashes off to cut grass to feed to her two cows. ‘This will take a lot of support from our government and a lot of initiative from our youth.’

Part of that support, Lydia believes, must come from agricultural extension workers who can connect young people to sources of credit or information. Mobile phones have filled this gap to some extent. But good-quality local knowledge is still lacking.

Dairy entrepreneur John Ngasha in Nakuru, Kenya

On her rounds, Lydia visits 37-year-old John Ngasha and his wife, 34-year-old Annie Ngugi, who run a farm outside Nakuru. A construction worker most of the time, John has a big and infectious smile.

He greets Lydia warmly under the shade of a tree. She has previously helped him navigate a sea of information to improve his small dairy business. He started off by buying two bulls, which he later sold for three dairy cows, so he can now sell milk.

‘I started this with little’, he says, glancing over at his three cows. ‘Sometimes I had no money at all. My family likes to drink milky tea. Ashamed that I had no money to buy milk, I decided to start keeping cows to have milk and to earn some money.’

‘I use Google to get knowledge’, he says, his smile growing into a grin as he flips open a smartphone from his pocket. He scrolls through a Farmer’s Guardian ‘meet the breeder’ video episode, highlighting prize-winning stock and what breeders look for in a champion breed.

Lydia has helped John adapt some of this information for his small farm. His books are in ‘excellent condition’, she says, leafing through the reams of notes and meticulous records John has kept to improve his animal stock and fetch more milk and income.

But John ‘borrows’ this land from his aunt who has emigrated, so he can’t grow feed on it. And while his three cows munch through 8kg of feed a day, costing around USD 2.70 a day, he earns just USD 4.81 daily from the milk they produce.

‘When you calculate what you have put in [keeping] the cow and what you are getting, it is very little. But I will try my best.’

© Georgina Smith

Renee Bullock, a gender specialist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), says these stories highlight a familiar struggle among young entrepreneurs. ‘Youth come into dairy for a whole variety of reasons’, she says.

‘And they each need different kinds of support. Some use dairy farming as a way to earn money after finishing school, or as a stepping stone to bigger opportunities such as dairy processing, or simply because getting a white-collar job didn’t work out.

‘But after investing heavily in their children’s education, Kenyan parents often expect their sons and daughters to pursue jobs outside of agriculture’, she notes. And young people often find themselves up against hierarchies and assumptions around what young men and women should do for their careers.

Yet around 80 per cent of Kenya’s dairy sector is made up of small-scale, informal dairy producers. Without support, high production costs and rising consumer demand for higher grade milk threaten to cripple small-scale dairy entrepreneurs.

Change could be on the horizon. With increasing pressure to pursue ‘low-carbon’ agricultural development in Kenya, support for dairy farmers who can help reduce harmful greenhouse gas emissions from their cattle is increasingly likely at the policy level.

Low animal productivity and low-quality feed make livestock greenhouse gas emission intensities higher in Africa than anywhere else. So supporting dairy farmers with improved feed and other strategies that lower their animals’ emissions is critical.

But Todd Crane, an anthropologist at ILRI, says meeting low-emission targets and reducing greenhouse gas emission intensity can be balanced with an inclusive approach to social benefits of low-emission development.

‘When we look at low-emission dairy practices, there is often little discussion about social distribution of benefits. Yet our research shows that intensification in agriculture and livestock development can tend to disenfranchise women, for example.

‘We want to give everyone—youth and adult men and women—options to make agriculture a viable livelihood. But to lower emissions intensities without creating more problems than we solve, explicit goals need to contain social inclusion targets alongside environmental targets.’

Some young small-scale dairy entrepreneurs like Samuel have already made the switch to this kind of more efficient, low-emission agriculture. But many more will require support to tackle the cultural, social and financial obstacles that stand in their way.

Meanwhile, farmers like John are doing everything they can to make ends meet. For them, dairy farming is one way out of poverty. Without financial assistance, his dream to become a dairy processor seems a long way off. But that won’t stop him. ‘I won’t give up’, he says.

Investors

Experts

You may also like

ILRI News

ILRI and Kenya Dairy Board sign agreement to transform the dairy sector ‘from farm to glass’

ILRI News

Farmer-to-farmer approach offers solutions to improve the efficiency of agricultural extension services in Kenya

ILRI News

Four-year initiative launched to improve milk quality, safety and marketing in central and western Kenya

Related Publications

Genetic relationships among resilience, fertility and milk production traits in crossbred dairy cows performing in sub-Saharan Africa

- Oloo, Richard Dooso

- Mrode, Raphael A.

- Ekine-Dzivenu, Chinyere C.

- Ojango, Julie M.K.

- Bennewitz, J.

- Gebreyohanes, Gebregziabher

- Okeyo Mwai, Ally

- Chagunda, M.G.G.

Estimation of genome-wide patterns of homozygosity, heterozygosity and inbreeding in crossbred dairy cattle population in Pakistan

- Un Nisa, F.

- Usman, M.

- Ali, A.

- Ali, M.B.

- Kaul, H.

- Asif, M.

- Mrode, Raphael A.

- Mukhtar, Z.

From protection to pollution: Evaluating environmental and human health risks of acaricide use in dairy farming in Kenya

- Maina, Kevin W.

- Parlasca, M.C.

- Rao, E.J.O.

Rift Valley fever virus remains infectious in milk stored in a wide range of temperatures

- Dawes, B.E.

- De La Mota-Peynado, A.

- Rezende, I.M.

- Buyukcangaz, E.K.

- Harvey, A.M.

- Gerken, Keli N.

- Winter, C.A.

- Bayrau, B.

- Mitzel, D.N.

- Waggoner, J.J.

- Pinsky, B.A.

- Wilson, W.C.

- LaBeaud, A.D.

Species diversity and risk factors of gastrointestinal nematodes in smallholder dairy calves in Kenya

- Cheptoo, Sylvia

- Yalcindag, E.

- Gordon, L.G.

- Rukwaro, Benson

- Kimatu, Joseph S.

- Wasonga, Joseph

- Karani, Benedict E.

- Ndambuki, Gideon

- Migeni, Susan

- Kagai, Jesse

- Kiprotich, Linus E.

- Saya, Nelson

- Vasoya, D.

- Nangekhe, Gertrude

- Onguso, J.

- Mungai, G.

- Bronsvoort, B.M.

- Cook, Elizabeth A.J.