India: Making milk ... in 24 hours

Posted on

by

- Douglas Varchol

- Thanammal Ravichandran

A newly developed variety of grass energizes one of India’s most successful women’s dairy cooperatives, showing promise to increase milk yields and quality and household incomes and, remarkably, to transform gender norms as well.

India is one of the biggest milk producing countries in the world, with most of the milk coming from small dairy farmers owning two or three cows or buffaloes.

Even though small in number per farm, between their feeding, cleaning, watering and milking twice a day, the dairy animals require a lot of effort, which usually falls on women.

But it’s an effort that can pay off handsomely for the entire household.

‘India has a big demand for milk and milk products’, explained Bhaskar Reddy, general manager of the Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy. ‘With its big population, it demands a lot of food.’

Rapid urbanization and a rise in household income are the main drivers for this demand. Clean, nutritious milk and milk products are good for kids and adults alike, and people are willing to pay a premium for them.

This booming demand is providing many opportunities for small-scale dairy farmers to benefit from new markets. But wide use of traditional dairy production practices, especially poor quality and quantity of feed, can’t keep up with this milk demand.

To help small dairy farmers exploit these new markets, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) teamed up with the Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy in a two-part pilot study investigating the impacts of a new green fodder variety on milk productivity, and how this forage might also improve gender equity in India’s smallholder dairy sector.

An all-women’s dairy cooperative

Started by women in 2002, the Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy has evolved over the years into one of India’s more successful dairy businesses, producing milk and milk products for the Mulukanoor regional area on a 24/7 basis.

In the beginning, the cooperative tellingly chose to call its milk brand ‘Swakrushi’, which means ‘self-help’, and developed marketing slogans claiming ‘Quality Milk is Swakrushi Milk’—which can be understood as ‘self-empowered milk’.

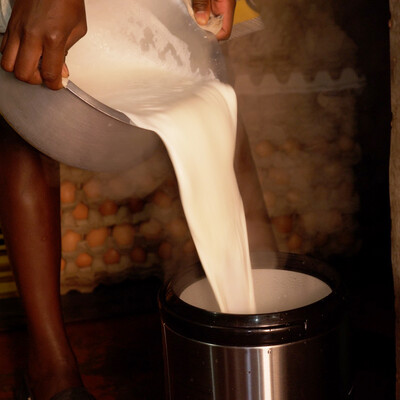

Each day, like clockwork, the cooperative’s 24,000-plus women dairy members rise before dawn to feed and milk their cows, producing over 58,000 litres of milk, which is collected twice a day at village collection centres.

From the village, the milk is then trucked to a modern milk plant where it is pasteurized, packaged and immediately distributed to local stores.

'When the cooperative first started, 90% of the milk was sold as liquid milk’, Bhaskar Reddy said, ‘and 10% was sold as value-added products like curd. Today, we are up to 25% of our milk being made into value-added products.'

Along with standard milk, diversified products include, among others, ‘toned milk’ with less fat than standard milk, and a full-cream milk with more fat, as well as ghee [clarified butter], sweet lassi [yogurt] and paneer [cheese].

'These value-added products are profitable’, Bhaskar Reddy said, ‘with the excess money they bring in going right back to our members as a bonus, which we pay out twice a year for the “Deepali and Dussehra” festivals so they have a little extra to spend.'

Swakrushi milk and milk products are very popular. Along with regular retail grocery stores, the cooperative has franchise opportunities for women to set up their own small retail businesses selling the products as well, and they are quite successful.

If you want fresh Swakrushi milk in your morning tea, best get to your local shop early before it sells out.

The Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy has won numerous federal and state awards for its remarkable success, but in the beginning, an all-women’s dairy cooperative was a new concept in India that struggled to be born.

Workers in the milk processing plant at the Mulukanoor Women's Cooperative Dairy, in Telangana State, India

Workers in the milk processing plant at the Mulukanoor Women's Cooperative Dairy, in Telangana State, India

Workers in the milk processing plant at the Mulukanoor Women's Cooperative Dairy, in Telangana State, India

Workers in the milk processing plant at the Mulukanoor Women's Cooperative Dairy, in Telangana State, India

Convincing the men

‘When we started the dairy cooperative in 2002’, explained Vijaya Reddy, chairperson of the Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy, ‘we began organizing with a few villages. Within four years, it was 52.'

But it wasn’t easy at first signing up women members because of the strong opposition from men.

There were two main issues the organizers faced.

‘First, they questioned, "Are you able to do this?"’ Sridhevi, quality control manager of the milk plant, recalled. “Is it possible for women to run the cooperative successfully? You have to work here all day and you can’t think about your kids at home.’

The village men were skeptical that women could successfully manage a complicated business like a dairy cooperative, with all its many moving parts. Women, they thought, should stay home to cook, clean and take care of the children. Period.

The second issue was more about money and personal power.

‘Men were afraid to lose their income’, Sridhevi continued. ‘They were fighting that they should get the milk payments.’

The men asked questions like, ‘Why can’t we become members? Are we not allowed to carry the milk and feed the cows?’ And—importantly—'Why can’t we get the money?’

‘It was our experiences dealing with already existing mixed men and women dairy cooperatives’, Vijaya Reddy explained, ‘that made our all-women’s cooperative dairy define itself from the beginning with strict rules.’

In the mixed men and women dairy cooperatives at that time, and even today, women are barely seen and hardly heard, and 90% of the money given to men for the milk payments never reaches the household, yet women do most of the milk production work. Consequently, the Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy’s founding principles established women-only membership, with women receiving the dairy money.

'Men got so angry when we started that they only gave milk to the government-based mixed dairy cooperative and not to the all-women’s dairy cooperative’, said Vijaya Reddy. ‘And then, slowly, some of the families came around.'

The change of heart came about because the organizers took the time to carefully explain to husbands and wives, together, that the dairy income could be better utilized if it went to women. After all, they reasoned, who takes care of the dairy animals and the children? Who is concerned about nutrition and education?

Many men reacted positively.

Ailaiah is the husband of Devendra, a dairy farmer who joined the cooperative soon after its inception.

‘When the village first discussed the all-women’s dairy cooperative’, Ailaiah explained, ‘I immediately gave my wife 100 rupees and told her to join.’

Ailaiah knew a good opportunity when he saw one. He and his wife were keeping a few cows to begin with, but they didn’t really have an outlet for the milk. The all-women’s cooperative was offering not only a new market but a good price for the milk, too.

‘I wasn’t angry about the woman-only membership requirement’, he continued. ‘Women are more motivated about children’s nutrition and education. And they need a good livelihood, too. So, I was in full support.’

Over the years, Devendra and Ailaiah slowly increased the size of their herd. They both stopped working as daily labourers and now they earn good money with their dairy farm. Even their son has returned home after graduating from college to become a dairy entrepreneur.

‘Within about two or three years, 90% of the villages were convinced that the women-only dairy cooperative was better at increasing the members’ income’, Vijaya Reddy finished up, ‘and that’s our journey through this male-dominated dairy cooperative system.’

Now, almost 20 years later, when a Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy outreach person goes to a new village to sign up members, word of the success and benefits offered by the all-women’s cooperative has preceded her.

Greening the fodder

Sridhevi started with the Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy 19 years ago. She was a science teacher at the time and felt inspired by the idea of an all-women’s dairy cooperative so she eagerly switched jobs.

Over the years, the dairy cooperative’s biggest challenge has been controlling the quality of the milk.

‘With the help of our extension personnel, it took us many years to make our famers understand that the quality of milk, and therefore the price they get for the milk, depends on fat content’, Sridhevi said, ‘and fat content is based on what they feed the dairy animals.’

When the cooperative first stated out, farmers would routinely feed their dairy animals crop wastes from the small plots of rice or maize they grew. But the quantity and the fat content of the milk produced wasn’t up to cooperative standards.

‘We introduced a lot of training programs for our members over the years’, added Swathy, a field extension officer for the cooperative, ‘especially how to care for and feed their dairy animals. And how to use mineral mixers and feed concentrates, too.’

Working with other institutes, the cooperative had made numerous attempts to promote green forages that often had limited impact.

For ILRI’s recent pilot project, the promising COFS-29 green grass variety, developed by the Tamil Nadu Agriculture University of southern India, was chosen for its high and fast biomass production and high biomass feed quality.

‘Dairy animals need two types of nutrients’, Vijaya Reddy said. ‘One is for maintenance and the other is for milk. For maintenance, you can manage with crop residues. For quality milk, you need more protein, and that’s where green grasses come in, particularly the recently introduced COFS-29.’

From an initial trial group of 25 women dairy farmers given COFS-29 training and seeds, word of mouth about the effectiveness of the grass variety quickly spread among the villagers. Within 18 months, close to 500 cooperative members were using it.

‘After feeding their dairy animals this new green grass’, Swathy said, ‘the feedback from the farmers was very positive. They produced more milk with a much higher protein content.’

After first cut of the grass, subsequent cuts could be harvested after 45 days instead of 50 or more for other green grasses.

COFS-29’s softer stem and lack of spikes also made it far easier to harvest and feed to dairy animals. Women didn’t cut their hands on the spikes like they did with other grasses, and its soft stem meant dairy animals could eat it directly without having to cut up the grass first. The spikeless fodder also made it easier for the animals to chew and there was little wastage.

Once there was sufficient adoption of COFS-29 among the village cooperative members, the ILRI pilot project was able to ask the gender part of its study question: What gender transformations, if any, did this new green grass variety have?

The answer?

Yes, definitely, the introduction of this new green fodder influenced gender norms and perceptions in three ways: time, knowledge and money.

Time

‘Usually women in the village graze their animals twice a day, every day, in the morning and evening’, explained ILRI researcher Thanammal Ravichandran, ‘usually near their farmstead or near the roadside where they can find a little bit of green grass.’

Grazing would take anywhere from three to four hours per day.

‘When ILRI introduced this new green fodder’, she continued, ‘they started planting it near their homesteads. Soon this three to four hours for grazing was reduced to about 20 to 30 minutes. The fodder was easy to cut, close to the house, and you didn’t need so much because the animals ate all of it.’

This freed up the women’s time to interact with family and community and to get involved in income-generating and leadership activities in the cooperative, increasing their visibility and status within these groups.

Kalavathi, a cooperative dairy farmer, for example, ran her dairy farm and had time to become chair of the local dairy cooperative, something once unheard of for a woman with little free time.

As the dairy business was becoming more profitable and less labour intensive than crop growing, men were now more willing to share the dairy burden with their wives to help gain more income for the entire household. And the men also gained extra time for themselves.

Women having free time for income-generating and leadership activities, and men helping women in their traditional role of harvesting forage, are two changes in gender norms brought about by this green fodder innovation.

Knowledge

'Before the women’s dairy cooperative started, women like my mother were invisible in society’, explained Suresh, son of Devendra, a member of the Mulukanoor’s all-women’s dairy cooperative since its beginning. ‘The cooperative taught women about dairy production; it gave them knowledge and authority to make their own decisions.’

Douglas Varchol

Knowledge enables. The original 25 women in ILRI’s pilot study learned all about COFS-29 cultivation and its use. They took this information and did something with it. They planted the fodder, fed it to their cows, saw their milk production increase and their incomes grow.

‘Previously, a man always used to think that he's the knowledge provider, he's to direct the woman’, said Thanammal. ‘When women have knowledge like how to feed and what to feed the animal, within her household, she gets respect.’

Men here are traditionally the ‘knowledgeable farmers’. With their adoption of COFS-29, women are now knowledgeable farmers as well.

This changed gender perceptions about who is a farmer with knowledge and who can make farm decisions. And the women’s bargaining powers within households increased with their increased knowledge.

Money

Women cooperative members milk their cows twice a day, seven days a week, and get paid for this effort every 15 days, without fail. This steady cash flow brings a stability to these households that is greatly appreciated by women and men alike.

Along with her job as quality control manager at the milk processing plant, Sridhevi keeps two cows with the help of her mother-in-law.

Keeping the cows and getting the extra ‘milk money’ in has been a big help in her household.

‘I get paid from my job at the end of the month’, she said. ‘I get the milk money every 15 days, which is helpful to pay day-to-day expenses. I have started saving this money. This has made my husband less worried now that I have money set aside.’

‘When women began getting more income’, Thanammal added, ‘men started feeling easy because it reduced his burden, that ‘Oh, I have to earn money.’ This increased income has helped to create some good relations between men and women within households.

In the past, only men were considered bread winners in the family. With the COFS-29 forage innovation, women’s dairy contribution to household income has become significant and visible.

What’s in store for the Mulukanoor Women’s Cooperative Dairy in the near future? Especially with the very real environmental concerns of raising livestock in a resource-limited world threatened by climate change and by other big social, economic and political problems maybe just on the horizon?

‘In my opinion, dairy production will not stop because milk is one of the most important nutrients for child development’, said Vijaya Reddy. ‘So the demand for milk will never decrease, but the production system may change.’

The wide adoption of the COFS-29 green grass variety, with its ability to increase both the quality and quantity of milk, is one way the dairy production system has already changed for the better, becoming more sustainable and efficient. Farmers are also routinely crossbreeding their traditional dairy animals with other breeds with good results; three higher yielding cows bred in this region now give as much milk as ten traditional dairy animals, thereby reducing methane emissions and waste pollution, further saving limited resources.

But is dairy farming a career path for a younger, more educated generation that gravitates towards good jobs in the bustling nearby mega-cities like Hyderabad?

‘Not all the children will leave the family; some will always show interest in dairy production’, Vijaya Reddy explains. ‘Techies are here starting farms already. The educated generation is already coming up with new innovations and technologies for producing more milk.’

Techies like Raju and his wife Sruthi are a typical young Indian couple. She has a college degree and he studied mechanical engineering. Theirs was an arranged marriage. He got a job in the city but didn’t really like the stress and felt it important to work for himself. He came back to his village with his wife and the idea to start a modern dairy farm.

‘My parents had one cow and concentrated mostly on crop farming’, Raju said. ‘I talked with many households to learn about the dairy business. I started with two cows. Now I have seven.’

Raju’s mother is a member of the women’s dairy cooperative and Sruthi plans to join soon herself.

In this way, they are both modernizing and keeping the dairy tradition going.

Investors

Experts

You may also like

ILRI News

ILRI and Kenya Dairy Board sign agreement to transform the dairy sector ‘from farm to glass’

ILRI News

Farmer-to-farmer approach offers solutions to improve the efficiency of agricultural extension services in Kenya

ILRI News

Four-year initiative launched to improve milk quality, safety and marketing in central and western Kenya

Related Publications

Genetic relationships among resilience, fertility and milk production traits in crossbred dairy cows performing in sub-Saharan Africa

- Oloo, Richard Dooso

- Mrode, Raphael A.

- Ekine-Dzivenu, Chinyere C.

- Ojango, Julie M.K.

- Bennewitz, J.

- Gebreyohanes, Gebregziabher

- Okeyo Mwai, Ally

- Chagunda, M.G.G.

Estimation of genome-wide patterns of homozygosity, heterozygosity and inbreeding in crossbred dairy cattle population in Pakistan

- Un Nisa, F.

- Usman, M.

- Ali, A.

- Ali, M.B.

- Kaul, H.

- Asif, M.

- Mrode, Raphael A.

- Mukhtar, Z.

From protection to pollution: Evaluating environmental and human health risks of acaricide use in dairy farming in Kenya

- Maina, Kevin W.

- Parlasca, M.C.

- Rao, E.J.O.

Rift Valley fever virus remains infectious in milk stored in a wide range of temperatures

- Dawes, B.E.

- De La Mota-Peynado, A.

- Rezende, I.M.

- Buyukcangaz, E.K.

- Harvey, A.M.

- Gerken, Keli N.

- Winter, C.A.

- Bayrau, B.

- Mitzel, D.N.

- Waggoner, J.J.

- Pinsky, B.A.

- Wilson, W.C.

- LaBeaud, A.D.

Species diversity and risk factors of gastrointestinal nematodes in smallholder dairy calves in Kenya

- Cheptoo, Sylvia

- Yalcindag, E.

- Gordon, L.G.

- Rukwaro, Benson

- Kimatu, Joseph S.

- Wasonga, Joseph

- Karani, Benedict E.

- Ndambuki, Gideon

- Migeni, Susan

- Kagai, Jesse

- Kiprotich, Linus E.

- Saya, Nelson

- Vasoya, D.

- Nangekhe, Gertrude

- Onguso, J.

- Mungai, G.

- Bronsvoort, B.M.

- Cook, Elizabeth A.J.