Adrian Hill, of the Jenner Institute at Oxford University, on the platforms and progress of global health vaccines

For those of you who, like me, are getting behind in your ‘vaccinology’ education and/or updates, here is a friendly, lucid and very current primer from Adrian Hill.

Hill was recently interviewed by Brian Perry, a former research leader at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) who chairs monthly webinars of the International Veterinary Vaccinology Network.

Adrian Hill is founder and head of the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford. That’s the institute that developed the AstraZeneca vaccine against COVID-19 and that worked hand-in-glove with the Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest manufacturer of vaccines, to get the AstraZeneca vaccine made and widely distributed.

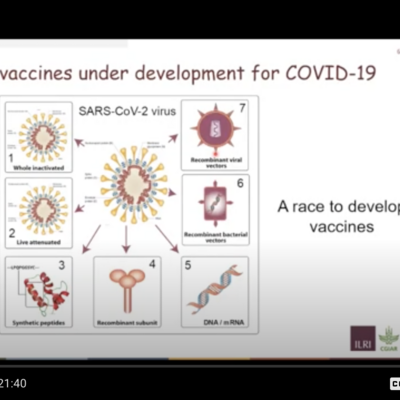

Hill gave details of the development by his Jenner Institute and others of two vaccines—one being the slowest ever to be produced—for malaria, work that has been going on for 111 years now, and counting—and the other being the fastest vaccine ever to be developed—which of course has been for COVID-19; this vaccine work took less than a year, from sequencing the virus to licensing vaccines.

Oxford's 'R21' malaria vaccine

Hill’s institute reported some two months ago promising results of their Burkina Faso trial of their ‘R21’ malaria ‘protein-adjuvant’ vaccine, which uses a virus-like particle in adjuvants that gives much high antibody responses than other malaria vaccine technologies. This R21 malaria vaccine has produced unprecedented efficacy for a malaria vaccine—77% efficacy against clinical disease—and is now in further and more elaborate Phase III trials in young African children. Results of the ongoing trials should be available in later 2022.

Hill’s group will be looking to get accelerated approval for their malaria vaccine, similar to the way in which every continent in the world gave quick approval to the COVID-19 vaccines now in use.

As (in 2020) there are about four times as many deaths from malaria as from COVID in Africa, there is a strong argument for governments to provide emergency use approval for this malaria vaccine.

Oxford’s R21 malaria vaccine is probably now the most effective one for African children and will probably cost about USD3 a dose.

Oxford's AstraZeneca COVID vaccine

Hill next turned to describe the unprecedented speed with which vaccine developers have produced safe and effective vaccines against COVID-19. Hill's group, led by Sarah Gilbert, developed the highly effective and widely used AsraZeneca vaccine against COVID and is now investigating a booster dose that may begin to be deployed in the UK and elsewhere in the coming months, use of the vaccine in children, intra-nasal ways to administer the vaccine, and the Delta and other variants that are arising.

The whole of the COVID vaccine effort, Hill emphasized, has been truly international in scope. Four of the vaccines in current use are from China, and one each were developed in India, Russia, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK.

We knew vaccine manufacture was going to be a bigger problem than vaccine design and development. There are nearly 8 billion of us on the planet and we need two doses each. If we include children, we need 10 to 16 billion doses for the world. We’ve never before done a fraction of that. So we tried to adopt a distributed manufacturing plan. AstraZeneca now has 20 manufacturers in 15 countries.

AstraZeneca is by far the most widely distributed COVID-19 vaccine at the moment: 184 countries have licensed and used our vaccine. 1.3 billion doses have been manufactured to date, most of this by the Serum Institute of India. The cost of our vaccines—USD3 per dose—is spectacularly low compared to the RNA vaccines and will stay low in low-income countries. And we are the major supplier to the incredibly important Covax program.

Where we have failed is being able to distribute the same number of doses to high- and low-income countries. There is stunning inequity, particularly for Africa. We just have to do better. We have to fix this ‘now’.

—Adrian Hill, Jenner Institute, Oxford University

Lessons from this COVID-19 vaccine work

What helped the most:

- Having done many vaccine trials before this pandemic

- Having good vaccine clinical trial centres

- Having a regulatory agency that’s not risk averse

- Having safety data on the vaccine technology

- Doing vaccine trials in different countries

What was most difficult:

- Manufacturing—the world doesn’t have the capacity to make enough vaccines to supply everyone in a pandemic (we’ve got to change that)

- Unresolved ethical issues—e.g., should countries allow vaccine to be deployed without efficacy data? (maybe; we need to come to a common view on that)

- Nobody knew how fast a vaccine could be developed (including the world’s leading experts on vaccines)

- Different regulators always requiring different things (that needs to be standardized because it slows things down considerably)

- Nations demanding that companies trial vaccines in their countries if they want to get their vaccines approved in their countries (that's pretty outrageous in a pandemic)

From the question-and-answers section that followed Hill's presentation

Perry: Why are vaccines against COVID-19 for children taking such a long time?

Hill:

Because of the huge ethical dilemma this presents. Vaccines are safe and immunogenic and appear to work in children—those are not the issues. The issue is lack of vaccine supply.

We have countries with just a few per cent of the people given just a single dose of the vaccine and only so much vaccine to go around. Should we be distributing those doses from wealthy countries that have over-ordered vaccines to people who are vulnerable in low-income countries or should we be giving those doses to all schoolchildren, from 12 and above or whatever, who, yes, are at risk of COVID but are very likely to get mild disease, with a very small possibility of long COVID?

If there was an abundance of supply, yes, you would vaccine all children. That would be straightforward.

But that isn't the situation. There is still limited vaccine supply and many people are arguing that those vaccines should go first to countries where most vulnerable adults have not yet been vaccinated.

Perry: The British Government has just cut its overseas aid. Would it not have been better for the government to use their funds to ensure that COVID-19 vaccines get into the low- and middle-income countries that desperately need them?

Hill: Definitely, the UK Government should not have cut its overseas aid. Hopefully, it will come back in a year or two. But this is similar to the question as to whether we should remove all patents to all vaccines tomorrow.

The answer is: If you removed all patents tomorrow, nothing would change for years. The problem is actual capacity to make vaccines.

Mr Gates tried to help organizations to make vaccines around the world, but he changed his mind by all accounts, because it takes years to build a vaccine development facility, to get it validated and approved for human vaccine use, and, not least, to recruit skilled staff. All of that is really important—but it's important for the next pandemic, not for this one.

What we need now is maximum productivity of existing vaccine facilities and it's getting better and better.

We're at five billion doses manufactured now. I think we'll be north of ten billion. If those vaccine doses were equitably distributed in the world, those 10 billion vaccine doses would crack most of the problem. As I said, most of the vaccine dearth is in low-income countries.

So that's what we can do now—countries that have over-ordered vaccine doses can export those to other countries to get fairer distribution.

Notes

The whole filmed interview is here: Global Health Vaccines: Platforms and Progress, International Veterinary Vaccinology Network webinar, 2 Sep 2021.

Your will find a wealth of COVID-19-vaccine-related news on ILRI's Expertise on Zoonotic Diseases website landing page.

Related news from ILRI on COVID-19 vaccines

Note: The list below of ILRI blog articles excludes our reporting on non-vaccine aspects of COVID-19, such as ILRI's large body of work on One Health, food safety and antimicrobial resistance. For ILRI's research and other publications on this topic, please consult our CGSpace document repository.

An update on COVID-19 vaccines, supply, performance and in-house tests, 6 Sep 2021

ILRI scientists and research partners contribute to growing body of knowledge on COVID-19, 1 Sep 2021

How COVID-19 measures have affected food safety in East Africa, 2 Jul 2021

Fauci, Doudna and Doherty offer 'pandemic science guide' at the Nobel Prize Summit last week, 11 May 2021

COVID-19: 'A terrible thing to waste'—One Health policy seminar, 10 May 2021

Peter Hotez at ILRI on vaccines and misinformation, 30 Mar

“A virus is a piece of bad news wrapped up in protein”—Sir Peter Medawar, 8 Feb 2021

Sounding the alarm: The impact of COVID-19 on global food security and nutrition, 26 Oct 2020

‘To turn the unknown into the known’: Inside the global effort to bring the fight to viruses, 24 Sep 2020

The world needs to learn how to live with COVID-19, says UK public health expert David Heymann, 3 Sep 2020

COVID-19 and the brain, 29 Aug 2020

The seven deadly drivers of zoonotic disease pandemics, 17 Aug 2020

A One-Health approach is needed to protect both people and the planet—ILRI and UNEP leaders, 14 Jul 2020

Unite human, animal and environmental health to prevent the next pandemic, says ILRI/UN report, 6 Jul 2020

‘A vaccine is coming—the question is how soon’, 11 Jun 2020

COVID-19 gives the ‘One Health’ approach to tackling epidemics ‘global celebrity status’. Again., 3 Jun 2020

A bridge not too far: To prevent pandemics, close the human and animal health divide, 30 May 2020

Diagnostic tests for COVID-19: How useful are they?, 28 May

‘A chance to reimagine life in a way that creates greater dignity for all’, an interview with David Nabarro, 20 May 2020

The German Federal Government supports Kenya’s efforts for COVID-19 testing, 18 May 2020

The good and not-so-good news about the state of COVID-19 vaccine development: A primer from ILRI, 16 May 2020

ILRI’s response to the pandemic: A deepening engagement with the press and policymakers, 19 Apr 2020

ILRI computing capacity made available to COVID-19 vaccine developers, 17 Apr 2020

What rapid COVID-19 antibody test kits can and cannot tell us, 15 Apr 2020

We need a new approach, or another coronavirus is inevitable—Jimmy Smith, 2 Mar 2020

Viral flash points? Poor urban settlements are highly vulnerable to the risk of the new coronavirus, 27 Feb 2020