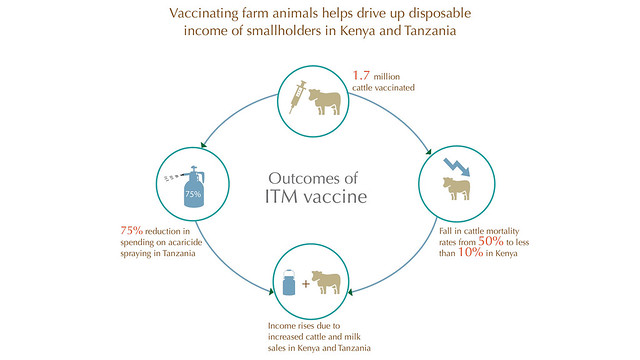

Vaccinating farm animals helps drive up disposable incomes

Wide-scale vaccination of cattle against East Coast fever would remove one of the biggest obstacles facing smallholders and herders trying to increase their meat and milk productivity. Endemic in 12 countries in eastern, central and southern Africa, the disease, transmitted by parasite-infected ticks, causes annual losses estimated at more than USD300 million and more than one million cattle deaths. While the vaccine was developed in the 1970s by the now Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO), recent research-for- development approaches have accelerated its uptake and demonstrated how its use is driving increased incomes for small-scale livestock farmers in Kenya and Tanzania.

Wide-scale vaccination of cattle against East Coast fever would remove one of the biggest obstacles facing smallholders and herders trying to increase their meat and milk productivity. Endemic in 12 countries in eastern, central and southern Africa, the disease, transmitted by parasite-infected ticks, causes annual losses estimated at more than USD300 million and more than one million cattle deaths. While the vaccine was developed in the 1970s by the now Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO), recent research-for- development approaches have accelerated its uptake and demonstrated how its use is driving increased incomes for small-scale livestock farmers in Kenya and Tanzania.

The vaccine, employing what is known as the ‘infection and treatment method’, involves infecting cattle with a ‘cocktail’ of live parasites and simultaneously treating them with a long-lasting antibiotic. This ‘live vaccine’ method generates life-long immunity to East Coast fever. Expensive, time consuming and difficult to produce on a large scale, it was not until 1996 that the first commercial batch was released by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). While ILRI produced another batch in 2008, uptake was slower than expected, with only 400,000 vaccinations by 2012.

Combating food insecurity and malnutrition through research to raise livestock productivity levels (Photo credit: ILRI/Bethlehem Alemu and Apollo Habtamu)

With a range of donors, a consortium of organizations set out to enhance access to the vaccine among livestock keepers in Kenya and Tanzania. ILRI has worked closely with the Global Alliance for Livestock Veterinary Medicines (GALVmed) to provide training and other support to livestock vaccinators, who in turn have immunized approximately another 1.3 million cattle against East Coast fever in both smallholder dairy and pastoral farming systems since 2012. With demand rising rapidly, ILRI and GALVmed supported the Malawi-based African Union Centre for Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases in producing two more batches. GALVmed expects a further one million cattle will be vaccinated by the end of 2018.

ILRI-led research in Kenya with 250 cattle keepers, vaccine distributors and veterinary staff found that vaccination against East Coast fever has led to a significant drop in cattle deaths, from 50% of cattle in affected herds to less than 10%, as well as to reduced household expenditure on regular acaricide spraying (anti-parasitic treatment) to keep the animals free of ticks. Healthier vaccinated animals produced more milk, fetched higher market prices and displayed increased immunity against other infections. The money and time saved on tick spraying allowed women to increase spending on household essentials (clothing, food, health, education) and to participate in women’s credit cooperatives.

In Tanzania, a study on the impacts of the use of this vaccine found that 167 small-scale farmers who had vaccinated their animals reduced expenditure on acaricide spraying by 75%. Other benefits reported included increased milk yields, reduced water usage, increased manure with which to fertilize croplands and better traction for pulling ploughs and carts from healthier animals.

Scientists, including ILRI and partner researchers, have taken a two-pronged approach to East Coast fever vaccine deployment and development; both have made substantial progress. The first approach focuses on decreasing wastage by reducing the number of doses per vaccination straw from 40 to 10. Once thawed and diluted, each straw needs to be used within four hours or discarded. This can be challenging as small-scale farmers have few animals. By reducing wastage, this method is expected to drive down the cost of vaccination per animal. The second approach harnesses the latest advances in biotechnology to develop proof-of-concept for a next-generation vaccine based on parasite molecules rather than live parasites, which should make it safer, cheaper and easier to manufacture and administer.

Henry Kiara, scientist, epidemiologist

This article was published in the ILRI Corporate report 2016—2017. Download the full report here: http://hdl.handle.net/10568/92517

Partners: African Union Centre for Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases; African Union-Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources; African Union Panafrican Veterinary Vaccine Centre; Animal Disease Research Unit, United States Department of Agriculture; Dulle Veterinary Centre; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; GALVmed; Institute for Genome Sciences, University of Maryland; Institute of Tropical Medicine, Belgium; Jenner Institute, University of Oxford; KALRO; Pharmavacs; Ronheam International Tanzania; Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh; Royal Veterinary College; Scotland’s Rural College; University of Copenhagen; University of San Martín, Buenos Aires; University of Toronto; University of Washington; Vetlife Consultants; Sidai Africa; VetAgro Tanzania; VetAid Kenya; Veterinary Council of Tanzania; Washington State University, Pullman

Investors: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; CGIAR Research Program on Livestock; Department for International Development, United Kingdom; United States Agency for International Development; United States Department of Agriculture