‘So what exactly are you researching anyway?’

A ‘pitching’ challenge at ILRI helps young scientists explain what they do—and why it matters—to inquisitive friends, donors and policymakers

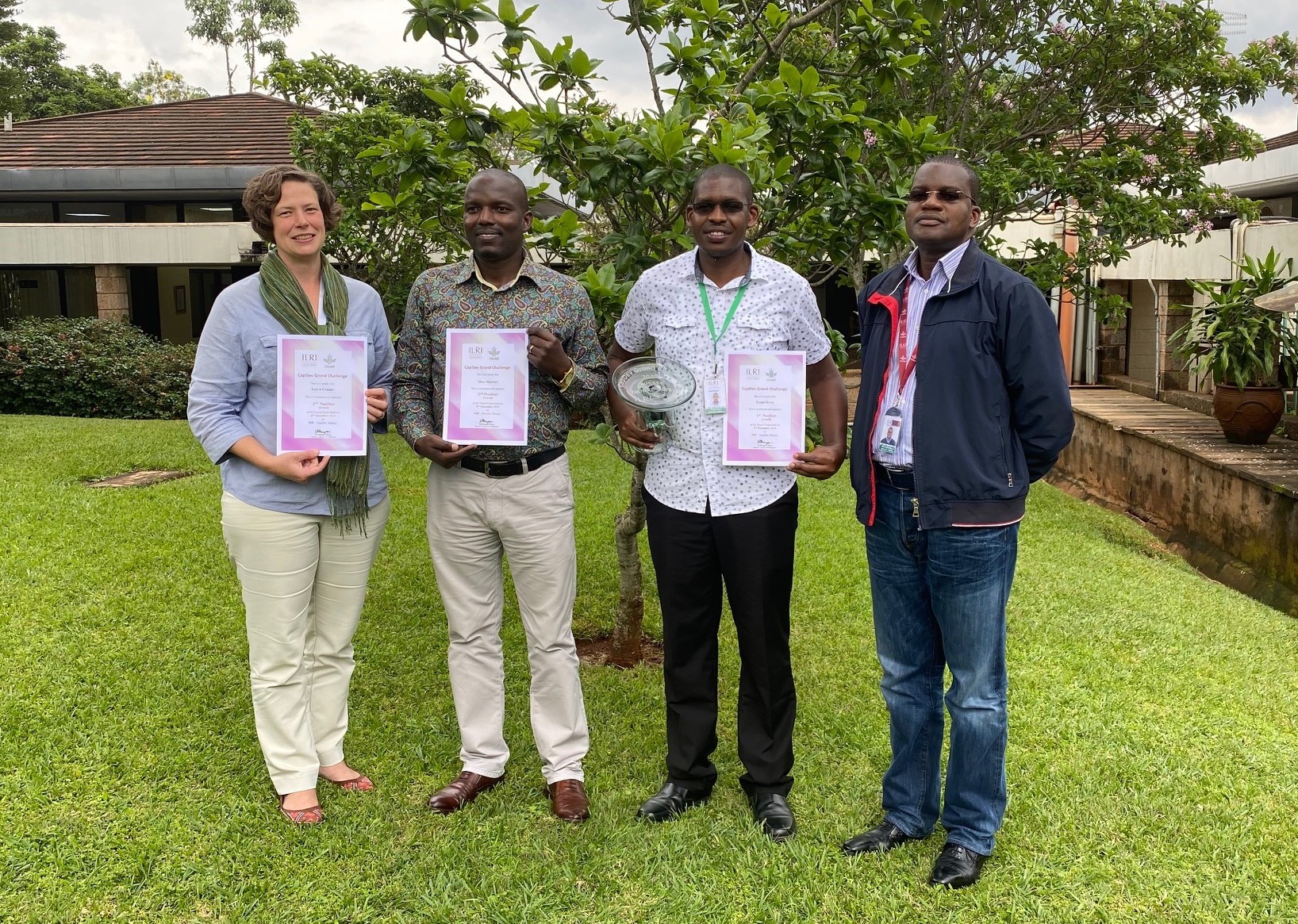

From left: Laura Cramer of Wageningen University; Titus Mutwiri of Jomo Kenyatta University; Daniel Korir of the University of Melbourne; and ILRI head of capacity development Ekaya Wellington.

Sometimes all it might take to prevent the spread of a contagious disease is to nail up a fence door left casually hanging open on its hinges. That’s one of the key lessons from Titus Mutwiri’s work on the spread of echinococcosis, a ghastly disease caused by a parasitical tapeworm that navigates through livestock, dogs and humans in the course of its lifecycle. (Mutwiri is a Ph.D. fellow from Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology attached to the animal and human health program, Zoolink project at ILRI.) Stray dogs gobble down the offal cast aside at porous slaughterhouses, inadvertently ingesting the parasite, and spread it through their faeces to other livestock or humans, causing a chronic, debilitating disease. Losses from the disease, especially in western Kenya where it is endemic, amount to millions of shillings a year; much of that could be prevented if the slaughterhouses were hardened and offal properly disposed of. (Of course, truly hardening a slaughterhouse and bringing it up to code requires more than simply banging a door shut—but simple, relatively cheap efforts like that or inoculating stray dogs against the parasite can go a long way toward reducing the incidence of the disease.) Mutwiri was the second-place winner of the 2019 CapDev Grand Challenge.

Twenty-five next-generation scientists at ILRI recently competed in the 3-minute research pitching contest for fellows. The contest celebrates the exciting work conducted by ILRI graduate and research fellows globally. Wellington Ekaya, the head of Capacity Development at ILRI, says the goal is to help the fellows learn to navigate ‘the “strange” landscape beyond academic research and the lab, and to help the young scientists develop the soft skills they need to effectively engage with broader audiences such as donors and policymakers’. The Challenge also aims at providing a vibrant platform for strengthening science communication among ILRI fellows, who eventually become ILRI, livestock and science ambassadors, among other critical roles in society.

The first prize went to a veterinarian who is attempting to quantify—and figure out how to mitigate—cow emissions in east Africa. Those emissions, especially the methane gas that cows burp out as the chemical price they pay for being able to digest grass, stubble and leaves, account for a significant share of the world’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—but precisely how much is still a matter of debate. One problem: Different breeds of cows, living in different ecosystems, emit vastly different amounts of the gas. Measuring how much GHG African cattle emit under different feed conditions is a big part of the work being done at ILRI’s Mazingira Centre, and for Daniel Korir, a veterinarian currently completing his Ph.D. at the University of Melbourne, almost as much a puzzle as a matter of concern. ‘We don’t yet have good measurements of African livestock’s contribution to methane gas production—but we do know that it’s relatively low’, he said. And the good news is that experimental feed, particularly of palatable leguminous fodder such as clover or alfalfa, contain secondary metabolites that can lower methane production.

Third prize went to Laura Cramer, a Ph.D. student at Wageningen University, who is attached to the sustainable livestock systems program/CCAFS. She is studying the interface between science and policy in regards to climate change and livestock in east Africa. How do local policymakers take in and use scientific information? How can knowledge brokers best communicate and share that information with policymakers? What other considerations and complexities affect the uptake of research, so that it becomes incorporated into national decision making? ‘I interviewed a lot of policymakers and scientists’, said Cramer. ‘But I also engaged in a lot of participant observation, trying to discern what evidence policymakers find particularly compelling’.

The contest was judged by a panel made up of a communication professional, donor, development policy expert and a scientist. The Challenge had another four categories—women in livestock research, biosciences, integrated sciences and the young motivators—and ultimately awarded prizes to 16 of the next-generation scientists. The contest was followed by a 3-day custom-made training on project impact pathways delivered by Wellington Ekaya. A second stage of training will focus on systems thinking, effective public engagement, proposal development and a host of related topics, and is planned for February 2020.