COVID-19 and the brain

Written by Annabel Slater

A woman in Mali wears a mask as a precaution against COVID-19 (photo credit: Flickr/World Bank Photo Collection).

A woman in Mali wears a mask as a precaution against COVID-19 (photo credit: Flickr/World Bank Photo Collection).

COVID-19 does not just affect the respiratory system – it is also linked to neurological diseases. Professor Tom Solomon, director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Protection Unity in Emerging and Zoonotic infections, and chair of neurological science at the University of Liverpool and the Walton Centre National Health Service Foundation Trust, UK, joined a recent ‘Round-up’ meeting of International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) staff to discuss what is currently known about COVID-19 and the brain.

The UK is at a more advanced stage of the pandemic than many African countries appear to be. As both an academic and clinical neurologist, Solomon recounted he has had to carry out more clinical duties than usual, with many staff off sick or shielding vulnerable family members.

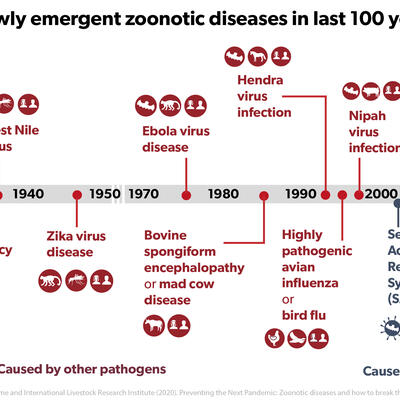

His research group, the Liverpool Brain Infections Group, have been able to recruit many people to studies through supporting collaborations across a network of hospitals in the UK, and the group also has many international collaborators, consolidated through the NIHR Global Health Research program, which supports health research directed towards people in low- and middle-income countries. The NIHR Health Protection Unit has been heavily involved in research for Ebola, Zika, and now COVID-19.

Solomon was in Malawi in January when he received news that cases of a disease resembling SARS were increasing in China. In response, a national protocol of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) was instigated by colleagues in Liverpool and elsewhere to collect clinical data. To date, this protocol has assembled a large amount of data from hospitals with over 75,000 people recruited to their study.

‘Based on our experience with epidemics of influenza, we expected COVID-19 might affect the brain too,’ said Solomon. CoroNerve, led by his colleague Benedict Michael, was set up as a surveillance network to collect data on neurological and neuropsychiatric complications linked to the virus. They were able to publish the first UK-wide study of neuropsychiatric complications caused by COVID-19, based on the first 153 patients, followed by a recent review in The Lancet Neurology of global studies.

They found that one common COVID-19 complication is altered mental state, which may be the result of encephalitis – swelling of the brain – caused by the virus itself, or by the body’s immune response to the virus.

They also found a higher incidence of cerebrovascular events, particularly strokes, in COVID-19 patients. The risk of stroke can be raised by many bacterial and viral infection, but COVID-19 also increases the stickiness of blood and can damage the cells lining blood vessels in the brain.

Exactly how COVID-19 can be distinguished as the cause of a stroke is a continuing area of research. In terms of awareness, Solomon suggested it could be up to local people to talk to governments and make them aware of the need to test neurological patients for COVID-19 infection. But he had no doubt that a rise in stroke incidence was no coincidence, saying that he was seeing large numbers of stroke patients with no previous known risk factors.

Solomon added that clinicians and scientists are invited to contribute data for a meta-analysis, and that more information could be found on the Brain Infections Global website. Currently, they have received data on 2,400 patients from 78 contributors worldwide.

Asked to comment on the course of the disease in the UK, Solomon said that while he felt lockdown could have been initiated earlier, the UK managed to avoid a critical shortage of intensive care beds by increasing the number of beds and setting up temporary hospitals.

In the UK, there have been reports that a high percentage of COVID-19 deaths are linked to black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. Solomon explained that it was not known yet whether there were inherent genetic factors that made these groups more susceptible, or whether it was due to other factors such as environmental risk factors.

Across the world, deaths related to the virus may have been counted in different ways, sometimes making international comparisons less clear. Solomon advised that a useful measure of COVID-19- related mortality would be look at the excess mortality of a country, compared to that of the previous five years.

Loss of taste and smell is a symptom which has now been recognized as a specific indication of COVID-19 infection. Solomon described preliminary data from other groups, suggesting that while some patients experience severe systemic disease, other patients will experience anosmia and it may be that these subsequently show mild cognitive impairments.

He also acknowledged that COVID-19 is linked to a rise in psychiatric disorders. Yet again, the cause is still under scientific investigation as such disorders could either be caused by the virus itself, or by the restrictions placed on people to contain the pandemic (or both).

ILRI’s director general, Jimmy Smith, had the closing question. Could anything be said about the long-term economic effects of the virus, as well as the social costs?

Solomon warned that there would be ongoing costs for patients with neurological damage in terms of requiring care. But we are also likely to see patients with ongoing costs due to lung damage, and long-term psychological impact. The numbers of people affected by COVID-19 is so great, that we will inevitably see an effect on all dimensions of all economies.

A monthly seminar providing the latest news about the link between COVID-19 and neurological complications can be found by visiting the Brain Infections Global COVID-Neuro website or following Professor Solomon on Twitter @RunningMadProf.